|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Category: icons

|

|

|

|

Heaven open on Holy Patmos

Posted on 02 May 2013, 3:49

Seven churches: Intro Pergamum Thyatira Smyrna Laodicea Philadelphia Sardis Ephesus Patmos

My sets of pics for this post: Patmos

Leaning against the ferry rail, the black water of the Aegean slid past below me, lit by the full moon high above. I saw dimly a small island shaped like a flat pyramid, darkly mysterious, as we sailed past. I leaned out and far ahead in the night were tiny lights – the lights of houses on the island of Patmos. It was 37 minutes past midnight and the words of John’s Apocalypse came into my head…

After this I looked, and, behold, a door was opened in heaven: and the first voice which I heard was as it were of a trumpet talking with me; which said, Come up hither, and I will show thee things which must be hereafter. And immediately I was in the spirit…

John, the author of the letters to the seven churches, was exiled here for his faith in the 1st century, and now, 2,000 years later, my father and I were arriving to complete our journey to this place where heaven was opened.

After our boat docked, we walked through sleeping streets pulling our cases on wheels. The hotel reception was closed, but five keys were on the counter with names sellotaped to them… none of them ours. So we took two at random and bedded down for the night.

I woke after an hour or two from a dream in which hundreds of people were walking up the street to our hotel, dragging their cases, the hundreds of rolling wheels filling the island with a great roaring noise, and all the people inexorably marching to claim the room they had booked and I had stolen.

Awake in the dark, it felt like a updated scene from the Revelation, with the Beast and the Whore of Babylon checking in their luggage. This island has something spookily spiritual about it.

Next morning, we walked down to the port town, Skala, which curls around a bay lapped by deep, transparent blue water. The sun was shining madly.

The town is all restaurants patrolled by cats, craft shops stocked with sponges and shells, narrow streets revealing whitewashed, domed churches, Greek men hurtling by on motorbikes, Orthodox priests flapping or pausing to pinch the cheek of a child, shop windows full of icons, fruit sellers at the harbour, men busy doing nothing at a taxi rank.

Over coffee at a streetside café we got talking to the owner and complimented him on the island. ‘It’s a beautiful place,’ I told him.

‘Yes,’ he agreed. And then with hardly a hint of smile: ‘But it is also a holy place.’

High over the town on a hill is the Monastery of St John the Theologian. Late morning a taxi bore us up a winding road through pine trees, past a stonemason’s yard with signs outside advertising petra and marmara (stone and marble), until we reached the Cave of the Apocalypse, below the monastery.

This is where the exiled St John received his Apocalypse, according to local tradition. And it is where our seven churches pilgrimage was completed.

It is 40 steep steps down to the cave and my father is 85, but he’s also intrepid and we made it down arm in arm almost without a pause. Over the doorway before you enter the cave is a bright icon of St John in red robes holding a pen in one hand while a pen holder is under his other arm. The book he holds is open at a page full of Greek text which reads: ‘In the beginning was the word…’

We stepped through the doorway and into the place where that word was alarmingly revealed. Although an Orthodox chapel has been added to the front of the cave, the powerful forms of the bare rock on your right are what immediately command your attention. The entrance to the cave is low, while the roof rises behind it, reminding me of a huge fireplace, which seems right. Holy fire touched down here.

In a deep recess is a place of prayer, marked by red velvet draped over the rock and hanging silver oil lamps above. The cave reminds me of the prophet Elijah in the Old Testament, who stood in the mouth of another cave and experienced earthquake, wind and fire, but found God instead in a still small voice. St John’s writhing visions seem to be the reverse of Elijah. They have nothing of the still small voice, but all of the earthquake, wind and fire.

And yet the atmosphere in the cave was quiet and expectant. We were there entirely on our own, which I think must be quite unusual.

A small window shows the view from the mouth of the cave. Below are the trees, fields, hills and bays of Patmos, and then the sea, and then the eastern sky. As he sat here, St John looked out towards the faraway seven churches of Asia Minor.

I sat with my father on a wooden bench and we prayed together. The cave has a beautiful acoustic. It is a place where the door of heaven opened for St John like the door of a furnace. In a small way, it opened for us too, but breathed only peace at the end of a journey.

Comment (0) |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Holy Saturday

Posted on 30 March 2013, 21:46

Holy Saturday is the forgotten middle day of Easter. Where Good Friday and Easter Sunday are full of action (and church services), Saturday is simply the day when Jesus lay dead in the tomb. It is the eye of the hurricane of Easter.

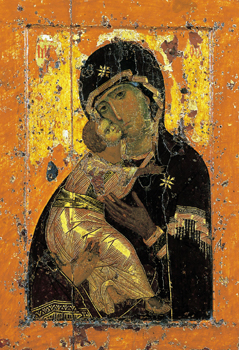

I was powerfully drawn to this 12th century Greek icon for Holy Saturday (above) when I first saw it in the 1980s. Greek icons normally show Jesus as a powerful, commanding figure. Even icons of the crucifixion are entitled, ‘The King of Glory’. But here we see Jesus broken in the ultimate weakness of death.

The image puts us in the tomb with Jesus. And there we see suffering. This dead face is set in a frown. There are dark shadows under the eyes – the shadow under the left eye is like a bruise. The shoulders are hunched and tense, while the arms are limp and useless. The body of Jesus looks like a media image of a torture victim.

But we also see vulnerability here. Jesus has the mouth of a sleeping child, with the lower lip sucked under the top lip, for comfort. The head is bent as if in sleep. We see the openness of Jesus to suffering and death. We see God made poor, weak and helpless. I don’t think there is any other image which shows this with such depth of emotion and insight.

The icon shows us the beauty of Christ in his obedience to the will of God, at vast cost to himself, and also in his unconditional love for us. Because it is for us, for our sake, that he is here like this. And this creates longing. The Orthodox liturgy for Holy Saturday, the day when this icon was carried through the streets, has a prayer which gives words to longing.

‘O faithful, come, let us behold our Life laid in a tomb to give life to those who dwell in tombs. Come, let us behold him in his sleep and cry out to him with the voice of the prophets: You are like a lion. Who shall arouse you, O King? Rise by your own power, O you who have given yourself up for us, O Lover of mankind.’

Comment (1) |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Born again fish?

Posted on 16 November 2012, 8:20

I went to Croatia a few weeks ago and visited the seaside town of Poreč (a name charmingly pronounced like ‘porridge’, but with a ‘ch’ sound at the end), which is home to a very ancient Christian church. Still standing is a modest, 6th century Roman basilica, which is quite plain inside except when you look to the front and see beautiful, glowing mosaics filling the semi-dome of the apse. In the centre of the mosaic is an image of Mary holding Jesus in her lap, with a smiling angel on either side. It is said to be the oldest surviving image of Mary in a western basilica.

But outside are even more wonders, because right next door to the basilica is the footprint of an earlier, 4th century church, which astonishingly still has its fine mosaic floor, open to the sky. The sea laps the shoreline less than 50 metres away.

Guard railings prevent you from actually walking on the floor (thank goodness), but you can easily see the weather-stained geometric shapes, flowers and foliage which fill the space. But there’s something else in the floor, and it’s a surprise. In the midst of all the patterns is a solitary fish. It’s rather randomly placed, top right in a big square that’s been sub-divided into a checkerboard of nine squares, three to a side. It’s as if a fish fell out of a shopping bag onto a highly patterned Persian rug and was left there for no particular reason.

I knew the basilica had this fish mosaic, and it was the main reason I wanted to visit Poreč in the first place. The fish is one of the earliest symbols of the Christian faith, dating right back to the times when Christians were persecuted and needed codes and ciphers to communicate safely with each other.

The word for ‘fish’ is ichthus in Greek, and the individual Greek letters can each be used to start a word which then forms the sentence, ‘Jesus Christ, Son of God, Saviour’. That’s how you turn an ordinary fish into a discreet little confession of faith. And of course this clever symbol has stood the test of time. You can buy cute versions of the same fish symbol and stick them on the back of your car to annoy the driver behind.

I was especially looking forward to seeing the fish of Poreč, because it was created in the same tumultuous century as the final persecution of the Christians, which was followed by the adoption of Christianity as the official religion of Rome. For that reason, this particular fish was made by men within living memory of the persecuted church, which gave birth to the symbol.

But two things took me by surprise. First, inside the basilica’s museum, you can see a copy of the mosaic close up. And I just wasn’t expecting to see a fish which looked so aggressive, with spines and needle-sharp teeth (see the picture above, or a bigger version here). The fish, after all, is meant to signify Christ himself. My wife Roey voiced what I was thinking: ‘That can’t be the ichthus fish because it looks so horrible!’

This made me think that maybe the leaflet we’d picked up at the ticket office, which described the mosaic as a ‘Fish – Christian symbol’, might be wrong. It could be that the fish was just a fish, part of the decoration of this ancient Christian building, which also features fruit and vines, flowers and leaves, without each detail being deeply symbolic.

The second surprise, though, was seeing the fish in the actual mosaic pavement, where it had been placed 17 centuries earlier. It is the only animal in the whole floor, and there it is, at the very front of the church. It simply stands out as something exceptional and eye-catching. As something significant.

Maybe it’s just there because the merchant who paid for this stretch of mosaic was in the fish trade and wanted to be remembered. But the symbol had such resonance for the newly-liberated Christian community that it’s hard to imagine it landed there on a tradesman’s whim, stripped of its cherished history and hidden meaning.

In a fishing town like Poreč, the makers of ancient mosaics knew what fish looked like, and they drew them as they saw them in the market, teeth and all. The craftsman who made this fish also depicted the gills like a wound in the fish’s side, using dark red stones.

I think this is a genuine ichthus – unlike the Disneyfied version seen today on a thousand bumper stickers.

See my Flickr gallery of the Euphrasian Basilica, Poreč.

Comment (2) |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

90 minutes with Moltmann

Posted on 14 March 2012, 6:21

Jürgen Moltmann has a very infectious way of laughing. He fixes you with his bright eyes, a smile spreads across his face as he’s talking, and then comes the almost soundless laughter that sweeps you with it. I really hadn’t expected that from one of the 20th century’s most brilliant German theologians, and even less so from someone who powerfully made the case, after Auschwitz, that God is a God who suffers.

I visited him at his home in Tübingen last week, after a 10 hour train journey. The magazine which sent me to interview him, Third Way, didn’t want me to fly by plane, for the greenest of reasons, but it was a long journey to make for a 90 minute meeting. It turned out to be beyond rewarding, though.

The French and then German countryside unfolding outside my train window was beautiful in the early spring sunshine, but I had my head stuck in a book most of the way. Like an undergraduate with a late essay to submit, I was deeply into Moltmann’s brick-sized autobiography, A Broad Place (408 pages), which turned out to be an inspiring read. By the time I sank into my hotel bed at 2am, I was ready with my list of questions.

Professor Moltmann retired in 1994, but since then, six new books of his have been published in English, with a seventh currently in the works. He’s now 85, but several years ago when he turned 60, he said that he unexpectedly ‘became young and lively again’. His youthfulness in old age seems to have stuck. The first sign I saw of it came after I climbed the road up and out of old Tübingen, along the valley above the River Neckar, and found that the car parked outside his house had personalised number plates. I spotted the ‘JM’ straight away.

Inside, after he’d made me a dish of very weak tea (I estimate Pantone 726), he took me into his study, which is a broad, beautiful, light-filled room looking down the steep slope of his long garden into the valley. I always enjoy seeing where people work, and this room, where so much influential thinking took shape, was everything you could wish for.

With no computer in sight, I asked him if he used an Apple Mac. ‘I am an old European,’ he replied, amused at himself. ‘I use telephone and fax.’ He writes his books by hand and corrects a typewritten copy. ‘I like the combination of mind and hand,’ he said, and then added, ‘At my age, I am writing more letters of grief and consolation, and I cannot type a letter of compassion.’

I’d asked to see his study because I wanted to know what pictures he had in there, as some of his thinking has been shaped by meditating on images such as Andrei Rublev’s icon of the Holy Trinity. He showed me a Greek icon of the resurrection on the wall, as well as a postcard image of Marc Chagall’s Yellow Crucifixion, which he had tucked inside a first edition of his book The Crucified God.

‘For a long time this picture was my companion,’ Moltmann wrote in his autobiography, ‘and was a symbol inviting me to theological thinking.’ I don’t know of many Western theologians who have done this.

At the end of our 90 minutes, I had to dash to catch my train home, but as I was packing up I couldn’t resist asking him what his favourite hymn was. It’s a bit of a cheesy Songs of Praise question, but I was interested in what a theologian would do with it. When he hesitated to answer, I expanded the question by asking what are his sources of inspiration and consolation.

‘Mostly watching nature – and especially the sea. From Hamburg, we always spent our holidays at the seaside. I was always fascinated and had mystical experiences! The music of the sea is like the tone of eternity. Because this was here before human beings came and this will be there when human beings have maybe vanished from the earth.’

I shot a video of the interview and will be putting some clips from it online soon. I’ll post here when they’re up.

Comment (1) |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Prayers from a dark cellar

Posted on 28 February 2012, 6:19

Last Wednesday, on the first day of Western Lent, I went down into the cellar of my house to clear out a small hidden recess. It’s round the corner from the steps down into the cellar and must be the darkest space in the house – and it was filled with kindling and bits of firewood. Many years ago, I used the recess as a prayer space, and there’s something in this year which is nudging me to pray there again.

Once I’d cleared out the wood, brushed down the flaking walls and swept the floor, I looked round the cellar for bits and pieces which would work as basic furniture for a would-be hermit. There was a chunky plank of wood by the electricity meter, so I cut it to length to make a low shelf, with two old paint pots (one at each end) to hold it up. I found a sawn-off block of tree trunk which was just begging to be sat on.

Then I brought down a candle, some sticks of incense, a Bible and a couple of prayer books, a hand-sized old Orthodox crucifix and a copy of an icon that has always meant a lot to me. And a box of matches, of course. Then I turned out the light and sat in the dark for about 15 minutes until my night vision started to pick up and I could make out a few fuzzy shapes. Although some dim, natural daylight filters down the stairs, this corner is plunged in near total darkness. So it was just me, God, and the occasional particle of light zipping through.

I first thought about creating a sacred space in the house when I read the journalist and theologian Margaret Hebblethwaite’s highly creative book Motherhood and God back in the 1980s. She made a place like this in a cupboard under her stairs, half underground.

|

|

|

|

|

|

Prompted by that, and by the Orthodox tradition of the icon corner, I’ve had a prayer space in my work room on the ground floor since the 1990s. But sitting in the dark of the cellar on Wednesday and lighting a candle, I immediately knew this would be the best place right now for the things that usually happen to me when I pray: feel God, feel nothing at all, get bored, get inspired, find peace, find turmoil – but most of all realise that just to sit here, putting myself where God can find me, is prayer itself.

And I like this symbolism. Prayer from underground, from the deepest part, in the rough foundations. Prayer from the inner workings – there is a labyrinth of old pipes above my head and a freezer behind me which quietly starts up and turns itself off every few minutes. Prayer in the dark, and from a place where you wouldn’t expect to find it. It’s nice to do something which might surprise even God.

I’m doing this because I’m not very good at prayer. But I’ve found over the years that the best thing I ever did about that was to set up my prayer corner, so that at odd moments I can go there to pray or simply to sit with God. And I’ve discovered, as Margaret Hebblethwaite did, that just to think of that place is prayer.

I’m hoping that having this more intense space in the dark, surrounded by the things which point me to God, will help me pray for friends who are going through truly hard times, and that it will bring a bit of fire to my weak faith.

|

|

Comment (0) |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Blessed are the body snatchers

Posted on 11 September 2011, 4:49

My lifelong fascination with ‘the far side’ of Christianity easily includes the Catholic Chuch’s love affair with relics, although I must confess some sympathy with it all. It’s a deeply human thing to show respect to what remains of those we’ve loved after they’ve died and the photographs, letters and books of people in my family which have come down to me are beloved things.

So the early Christian practice of meeting at the gravesides of the martyrs and placing their portrait paintings in churches seems absolutely right to me, even though it’s not for everyone. But what about collecting bones and skulls, inspecting the bodies of dead saints and parading their body parts through the streets? Call me squeamish, but it just seems macabre and obsessive, not to mention terminally out of step with modern culture. Believing the Christian faith is hard enough these days without throwing in veneration of the big toe of St Bob the Bizarre.

Back in May this year, a syringeful of John Paul II’s blood, taken from him before he died, was venerated in his beatification mass in Rome, while another found its way to Krakow in Poland. His body has already been moved upstairs from the basement of St Peter’s into the church, and it’s a disturbing possibility that the Vatican’s resurrection men might be visiting his coffin for bits and pieces sometime in the future.

Which is why I was curious to get hold of a copy of a new book, Saints Preserved: An Encyclopedia of Relics, by Thomas J Craughwell. This is a book which knows where the bodies are unburied. If you want to get on a plane to go and venerate one of the many skulls of St George, the Holy Bench Jesus sat on during the Last Supper, the eye of Blessed Edward Oldcorne (don’t ask), the humerus of St Francis Xavier or even the skis of John Paul II, this is where to start.

I’m disappointed though that Craughwell doesn’t pass much critical comment on the history or authenticity of the relics he lists. Many of the saints’ relics are genuine, but all the claimed biblical objects must be regarded as frauds perpetrated on credulous believers.

It’s a fraud the Church has colluded in over the centuries. Take the Holy House of Nazareth, for example, where Jesus, Mary and Joseph lived, which was flown by a team of house-moving angels to Loreto in Italy in the 13th century. A virtual queue of Popes visited the house to bless it and bestow privileges, and only Julius II demurred by adding the words, ‘as is piously believed and reported’ to an account of the shrine’s legend.

However, there are some signs of change, as witnessed by the curious story of the Holy Prepuce (the foreskin of the infant Christ), which was the subject of another book, An Irreverent Curiosity, which I read a few months ago.

According to the book, written by American journalist David Farley, the Holy Prepuce was venerated every January 1st (the feast of the circumcision of Christ) by the people of Calcata, an Italian hill town. This went on for almost four centuries without a problem until 1900, when Pope Leo XIII took the highly unusual step of censoring all mention of the relic on pain of excommunication. The blessed foreskin had become an almighty embarrassment. But then things went further.

In 1983, the priest of Calcata told his congregation that the Holy Prepuce had been stolen from the shoebox in his wardrobe, where he had kept it for safety, and it has never been seen again. Locals believe it was snatched by Church officials to be ‘disappeared’ into the Vatican. Other uncomfortable relics, such as the breast milk of the Virgin Mary, have also been sent into retirement.

Like most traditional elements of Catholicism, the cult of relics has been enjoying something of a revival under John Paul II and Benedict XVI. Their Church has renewed its love of bloodstained shrouds and holy bones. For them, God moves not only in mysterious ways, but in medieval ones too.

Comment (0) |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Devotion by design

Posted on 31 July 2011, 23:28

I skipped church this morning and went to see the National Gallery’s Devotion by Design exhibition instead. It wasn’t a bad swop, as the exhibition is about Italian altarpieces from before 1500, and these amazing creations were presented in darkened rooms with the sound of liturgy and music in the background… all very atmospheric.

The exhibition, which runs until 2 October, is quite ‘how to’. That is, it’s very interested in how these multi-image pieces were constructed, allowing you to poke around behind two huge altarpieces to see the carpentry beneath their glittering, golden faces, and the surgery they have endured over the centuries.

One room explains how the people who commissioned and paid for the altarpieces imposed their own choice of saints and sacred stories on the artist. If there was more than one institution commissioning the piece, then the haggling over the cast list of who should appear in the picture could go on for a very long time.

What I missed was a good explanation of the role of altarpieces in church worship, or their impact on the ordinary worshipper. After all, in the age before television and giant advertising images, these pictures must surely have had huge impact, especially as they were positioned so you were looking right at them during the high point of the eucharist. The hyper-realism of some of the painting also draws you into an encounter, despite yourself, with the saints shown there.

I leafed through the exhibition catalogue in the shop afterwards, and it had good material on the place of altarpieces in the church’s liturgy, so it’s a shame that wasn’t reflected in the exhibition itself.

That said, Devotion by Design is thoughtful and intriguing, especially if you’re interested in the construction, technique, negotiation and contracts that underlie these powerful images used in Christian worship.

Comment (1) |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Jesus shops at Walmart

Posted on 26 July 2011, 9:07

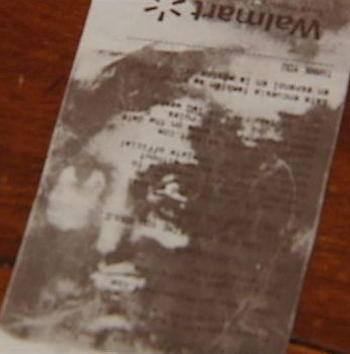

A South Carolina couple, Jacob and Gentry, went shopping in Walmart for pictures a couple of weeks ago. They found a picture which made headlines around the world, but it wasn’t one of the ones they bought in the store. Because a few days later, as Jacob was walking out of his kitchen, the Walmart receipt, lying on the floor, caught his eye. It had strange, dark markings on it.

‘It was like it was looking at me,’ he said. ‘The more I looked at it, the more it looked like Jesus.’

Stories of Jesus appearing on household objects are two a penny on the Net. It’s a rare month when Our Lord isn’t turning up on a tortilla or a cow’s udder somewhere. Such reports trigger a torrent of comic tweets, as well as punning headlines in newspapers. One appearance of Jesus in a British steak and kidney pie produced an inspired headline in The Sun newspaper: ‘Jesus Crust!’

Curiously, spontaneous images of Christ have a long history. One early legend, dating back to the 6th century or maybe earlier, tells of how Jesus turned down an invitation to pay a visit to the King of Syria. He RSVP-ed by sending the king a cloth he had used to wipe his face. When the king opened it, the face of Jesus was printed on the fabric.

Art historians say legends such as this were developed to provide much needed theological support for the explosive growth in popular images of Jesus, Mary and the saints. Christians of the time were using mass produced holy images in highly superstitious ways, hanging them up in their homes and workshops as good luck charms. Those who championed this popular devotion promoted the legends in a brilliant (and ultimately successful) piece of PR, saying that images were ok because they originated in a miracle of Jesus himself.

With all due respect to Jacob and Gentry, Christians who get excited about God performing a conjuring trick with a Walmart receipt are also perilously close to crossing the line between miracle and magic.

One of the questions always raised by stories such as this is why a stain looking like a man with a beard should always be identified in the media as Jesus? People posting comments on blogs and Twitter over the past week said they saw Charles Manson, Josef Stalin or Rasputin, rather than Jesus. ‘Even a blind person can see that this is Osama Bin Laden,’ said a commenter called gotjapanka on YouTube.

But Christianity has form in this area. Stories of plaster saints which weep and bleed – and even wink or lactate – are still quite common, and although they can also occur in Hinduism, for example, it is the Catholic stories which are strong in Western folk memory.

Even though Christians brought up on Monty Python are able to laugh at reports of Jesus and Mary appearing on a pizza near you, I think many believers are slightly beguiled by the stories almost to the point of wishing they were true. There are good reasons for this.

Firstly, these visitations are invariably tacky. I’m thinking of the toasted cheese sandwich which looked vaguely like the Virgin Mary and which ended up being bought by an online casino for $28,000. And also the Jesus-shaped shadow cast by a tree on a caravan park fence in Australia which caused the person who saw it to exclaim ‘Jesus Christ!’ – and not in a holy way.

These are tales of transcendence meeting trailer park. That is what makes them hugely entertaining, of course, but it also has a certain appeal to Christians, because holy things appearing in humble locations is what the faith of Jesus is all about.

Added to that, the images suggest God is breaking out of organised religion and into the grittiness of everyday life. One comment posted on Huffpost Comedy made a fair point when it said, ‘God appeared to Moses as a burning bush, as a pillar of fire to the Israelites, as an angel to Abraham etc… and we get a Walmart receipt?’

Well, yes… but isn’t that so New Testament? Jesus was born in a barn. So is it any surprise that he shops at Walmart?

If Jesus is going to appear anywhere today, then a pizza shop, supermarket or casino sound exactly right.

However, any Christian tempted to believe that God engages with us today via fuzzy images of a man with a beard should remember some of Jesus’ last words to the first disciples. He told them to go into all the world. It is surely through flesh and blood human beings, rather than stains on checkout receipts, that Jesus touches the earth now.

Comment (0) |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Treasures of heaven

Posted on 07 April 2011, 2:23

I went yesterday to the British Museum’s press launch for their major summer exhibition, Treasures of Heaven. The show promises to shine light on one of the most curious – not to say bizarre – aspects of the Christian faith: the devotion shown to relics.

Statues of saints and their relics were smashed or forcibly removed from British churches in the 16th century Reformation, and might seem like an obscure historical footnote now. But as Neil MacGregor, director of the BM, pointed out at the launch, relics were hugely significant objects in medieval Europe, bringing power, prestige and wealth to towns and cities, especially if they became the destination of pilgrims.

Talking about one of the exhibition’s star relics, a thorn said to be from Christ’s crown of thorns and housed in a kitschy gold reliquary (seen above), MacGregor quipped that ‘at the second coming, Christ would make a point of coming to Paris to collect his thorn.’ It was this kind of belief about relics which put medieval cities on the map.

The exhibition will bring together relics, reliquaries, manuscripts, prints and pilgrim badges from more than 40 institutions around the world, including the private chapel of the popes in the Vatican. The chapel is sending the Mandylion of Edessa (or a 5th century copy of it, at any rate) which is rarely seen in public, so that will be an event in itself.

I was told that staff at the museum are expecting some visitors to venerate the relics during the show.

Karen Armstrong, also at the launch, talked about the difficulty of relics for post-Reformation people. In fact, she said they were possibly ‘rebarbative’ (repellent) in modern culture, not a word you hear every day. The pilgrims who travelled to venerate the bones of saints and martyrs ‘confronted death but also discovered something which transcended death.’

She recalled the death of Princess Diana and how people lit candles and heaped up bouquets of flowers on the streets, ‘so that London seemed like India because of the smell of rotting vegetation!’ The cult of relics and the cult of celebrity may be a lot closer than we think.

Treasures of Heaven will run from 23 June to 9 October and tickets are now on sale.

Comment (0) |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

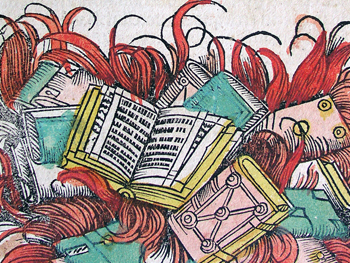

Burning holy things

Posted on 06 April 2011, 3:07

Pastor Terry Jones of Florida finally got to burn the Qur’an on 20 March, months after he put the holy book on death row and despite appeals for clemency from Barack Obama. Bizarrely, Jones’s church, the Dove World Outreach Center in Gainesville, Florida, subjected the Qur’an to a show trial, and four forms of execution were considered: burning, drowning, firing squad or shredding.

I don’t think shredding was available in medieval times (thanks be to God for that), but the popular practice of burning, always such a crowd-pleaser back then and a favourite of the church, won out in the end, and the Qur’an was soaked in kerosene and burned to a crisp.

As a direct and easily forseeable consequence, protests were sparked in Afghanistan and five UN staff killed, allegedly by agents of the Taliban. Pastor Jones, clearly a man of limited imagination as well as charity, is reported to be unrepentant.

Writer and publisher Jon M Sweeney wrote an interesting piece in the Huffington Post in response, reflecting on the correct way to dispose of unwanted holy books. Copies of scripture which are worn out are honourably buried and shown the respect given to human beings when they die, he said. This is how old and ragged scrolls of the Torah are laid to rest, as well as ancient copies of the Qur’an.

Jon Sweeney himself has buried Bibles with cracked leather covers and well worn pages in his back garden, and he imagines future owners of his house puzzling over what they find when they do some gardening.

The respect normally given to the scriptures of almost all religious traditions highlights the incredible shock value of Pastor Jones’s Qur’an burning. When violence is done to a book which is normally treated with reverence and care, the impact is emotional.

Jon Sweeney’s piece reminded me of something I’d read a long time ago about orthodox icons and what happens to them when their images fade beyond recognition. I actually have an old icon in that state, and I’ve been reluctant to simply throw it away. How are sacred objects treated at the end of their working lives?

Fr David Moser, a Russian Orthodox priest in Indiana, asks ‘what then do we do with those things – dried bread, old icons or other holy items – of which we wish to dispose in a respectful manner? Such things should be burned and then the ashes buried in a place where they will not be walked upon.’

The Russian Orthodox Cathedral of St John the Baptist in Washington DC agrees: ‘A holy item, even if it has lost its original appearance, should always be treated with reverence.’

But it wasn’t always like this. Writing in the 7th century, this is how St Leontius, a bishop of Cyprus, defended icons against the charge that they were idols: ‘If it is the wood of the image that we worship as God… then we would not throw the image into the fire when the picture fades, as we often do. And again, as long as wood is fastened together in the form of a cross I venerate it because it is a likeness of the wood on which Christ was crucified. If it should fall to pieces, I throw the pieces into the fire.’

Leontius’s approach sounds very straightforward and robust. His description of ‘throwing the image into the fire’ does not sound like disposing of something ‘in a respectful manner’ to me. Possibly he is exaggerating in his eagerness to show that icons are not idols. Or maybe his bonfire of old and unwanted icons reflects a time when sacred objects were handled with more confidence and less fear.

Either way, how we behave towards the precious and revered objects of our own faith and other faiths, and why we do it, deserves careful thought.

Comment (0) |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Heaven and hell in a country church

Posted on 09 October 2010, 4:47

Flying to Byzantium: Entry 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | Photos

Istanbul, Sunday: Tali and I emerged from the depths of Hagia Sophia and went to sit in the open air café in the gardens outside for a calming cup of coffee and cigarette after all that religious intensity. I don’t normally smoke, but it was definitely time for some nicotine-assisted reflection.

Meanwhile, great dollops of beautiful warm sunshine were being generously served up on Istanbul, and after a quick visit to a cash machine, followed by a stroll among the underground pillars of the Byzantine cistern of Yerebatan, which is across the road from Hagia Sophia, we jumped into a yellow taxi.

‘Can you take us to the Chora Church?’ I asked our small, moustachioed driver. ‘Yes,’ he replied. And then sped off in the opposite direction to the church.

There followed some back seat angsting over whether we were being taken for a ride, until our driver explained that the police had closed the obvious routes because the town was choked with tourists. We drove around the Saray point and up the Golden Horn, with more than enough to look at on the way: towering, historic mosques, noisy, colourful markets, people enjoying lunch on the street, sticking their faces into chicken kebab wraps, ferries roaring out into the lively waters around the Galata Bridge.

Ten minutes later and we swept left along a broad road and were suddenly alongside the massive medieval walls of Constantinople, looking at them from the outside, just as the Ottoman attack troops had done before the city fell to them in 1453. And then left again, through a great breach in the walls, and we dropped down a narrow street to St Saviour’s, the Chora Church.

One of the meanings of chora is ‘country’, and as this whole area was rural even into the 20th century, the Chora Church is basically the ‘country church’. Which sounds very sleepy to English ears – and there is something country in feel about this place. It has a shady, walled garden at the back, and over the wall I could hear a children’s playground. But far from being just another country church, St Saviour in Chora is a jewel of Byzantine art: rebuilt in the 11th century and then decorated with the most stunning mosaics and wall paintings during a six-year makeover in the 14th century.

If that sounds a bit serious, then stepping inside makes you realise it’s entertaining, too, because the scenes covering the walls and ceilings of this lovely building are full of incidental detail: the water jars being topped up at the wedding feast of Cana; children playing on the edges of the crowd in the feeding of the 5,000; an angel carrying a giant scroll with the sun and moon rolled up in it at the last judgment. This is medieval television and the glass pixels in the mosaics are tiny enough to make it hi-def.

As you walk into the church, you pass beneath a monumental head and shoulders of a fierce-looking Christ. This is titled, ‘Jesus Christ, the chora (land) of the living’. So you enter under a theological pun which plays with the church’s name and the words of Psalm 27: ‘I am still confident of this: I will see the goodness of the Lord in the land of the living.’

But the face remains powerful. In her book, The Irrational Season, Madeleine L’Engle describes visiting the Chora Church and seeing this image of Christ. She says, ‘I knew that if this man had turned such a look on me and told me to take up my bed and walk, I would not have dared not to obey. And whatever he told me to do, I would have been able to do.’

Like Howard Carter at the opening of Tutankhamen’s tomb, we saw ‘wonderful things’ as we walked around, but I was here mainly for one wonderful thing: a fresco I had seen long ago in a book and which has lodged in my heart and head ever since. I saved it for last. It’s in the church’s burial chapel, painted inside the half dome at the east end, filling the whole of that curved space.

Standing dead centre beneath the icon, Tali and I looked up and became for the moment its intended viewers. Its title is Anastasis, ‘The Resurrection’, and in it the most alive Christ you’ve ever seen strides through hell, seizes Adam and Eve by the wrists – just as you’d grab the wrist of a difficult child – and pulls them bodily from their tombs. Beneath his feet are the trashed gates of hell, and below that is Satan, bound like a slave and surrounded by broken locks, chains, jailer’s keys and other small debris from the infernal workshops.

But it is Jesus who commands the scene, and your attention. I’ve never seen him painted this way. Byzantine icons are famously formal and still, with the look of people who have been told to hold a pose and not move. But this Jesus is caught in swift and decisive movement. He captures the vigorous words of the Orthodox Easter liturgy…

Christ is risen from the dead,

trampling down death by death,

and to those in the tombs he has given life.

This is so far from the seven-stone weakling Christ I saw pinned up in Sunday school in the 1960s, and so far from the bleeding victim Christ of Catholic statues which weep, that it took my breath away when I first saw it. Like reading Mark’s Gospel, it made me want to follow Jesus then… and now.

Did Jesus rise from the dead? I don’t know. What I do know is that I’d trade just a glimpse of this image for a hundred evangelical books which try to argue ‘the case for the resurrection’ like a whodunit. The Christ shown here powerfully makes me want to believe, and my unbelief can go hang.

Having said all that, I stood still under the image: absorbed, gazing, listening in the few minutes of my life I was there. Madeleine L’Engle says she trembled with joy as she stood on the same spot. For me it was wonder freed from emotion, which I hadn’t expected.

I don’t know if I’ll ever be here again. But I live in the glow of it. I hope for the life and transformation promised here. I hope to be in the land of the living Christ.

Comment (3) |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Into the Mega Ekklesia

Posted on 06 October 2010, 7:19

Flying to Byzantium: Entry 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | Photos

Istanbul, Sunday: Up at 7.30, along the gloomy corridor to the hotel lift, and then up, the lift managing no more than a crawl, to the 8th floor. The doors opened and the sun burst in, and we walked out into a rooftop breakfast room floating above the city, with the whole sweep of the Sea of Marmara at our feet.

Tali and I sat dazzled by the light and hardly able to drag our eyes away from the view. The Marmara really is a handsome body of water, with the Prince’s Islands forming beautiful grey silhouettes in the eastern light, 10 miles distant across the silky water. The islands were so-named because unwanted minor royals were often dumped there in Byzantine times, with no access to Hello! or Grazia and the other essentials of celebrity.

Breakfast over, we took the tram to the Sultanahmet (the ‘Hippodrome’) district of town, which is the historic centre of old Stamboul. There we went straight to Hagia Sophia and entered the gardens on the west side, which have been turned into an orchard of ancient stone columns, each dug up at various sites around the city.

I could hardly bear to go into the Mega Ekklesia (the ‘Great Church’ as it was known almost from the time it was built in the 6th century), as I’ve imagined the moment for so long, so we loitered around the gardens first, admiring beautiful pieces of long destroyed buildings, some of them in such good nick they might just have come out of the sculptor’s yard.

But then we turned to the imposing doors and passed through the outer and inner porches and on into the church. The interior is such a delirium of space I had to lean against the doorway for the first few minutes to drink in what I was seeing.

Below, a polished marble floor of vast expanse; above, the dome ringed by its 40 windows, sailing weightlessly into heaven as it has done for 14 centuries; around me, a hundred arms raised… not in worship, but holding digital cameras. In the centre of the church, huge chandeliers hanging from the heights above to hover within touching distance of the people below, creating intimate pools of space.

Unlike all the domed cathedrals I’ve visited, here the dome is immediately visible from the church door, and so the visual impact of Hagia Sophia arrives at once, in a single, overwhelming instalment.

In the 10th century, a Russian prince sent ambassadors to Constantinople in search of a faith to replace his paganism. When they arrived in Hagia Sophia, they said, ‘We knew not if we were in heaven or on earth, for surely there is no such splendour or beauty anywhere upon earth.’

A thousand years on, and even though the church is now stripped of the Christian worship which once made it live, I can understand what they meant. Its vast spaces, its beauty and antiquity, even its faded grandeur and tangible sadness, all evoked in me the mystery and eternity which belong to God.

We walked up an ancient spiral ramp to the gallery, which gives stunning views down into the church. At this level you can see how the eight large medallions bearing Islamic calligraphy are constructed, each of them with a wooden framework. The medallions were only put in place in the 19th century by the Swiss architect tasked with restoring the building.

They complement the calligraphy right up at the highest point of the dome, which carries a famous verse from the Qur’an: ‘God is the light of the heavens and the earth’ (Surah 24:35). No Christian could argue with these words, but there is controversy over whether the calligraphy should be removed as it’s believed a much older mosaic of Christ lies beneath it. Christians of a more Puritan temper would probably side with Muslims on this one.

Beyond a marble screen in the gallery, I found the luminous icon of Christ which has been made famous on a thousand postcards, book covers and printed icons. The 14th century mosaic is next to a window and is thought to have been damaged by rain, so large areas of the jigsaw of tiny mosaic pieces are missing, but the heads of Jesus, plus Mary and John the Baptist, who stand on either side, are intact and beautiful. Each of them is shown against a glowing gold background in the world of eternity.

I was lost for a while in thought and maybe even prayer, standing before this noble and searching image of Christ. Just to stand before it is to be given dignity. And then I rejoined the crowd there, snapping like paparazzi before one of the surviving glories of lost Byzantium.

Comment (0) |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Flying to Byzantium

Posted on 02 October 2010, 4:44

Flying to Byzantium: Entry 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | Photos

Tomorrow morning at dawn I fly to Byzantium with my daughter Tali for a couple of days in the great city. I always had in mind that I’d travel there by train, as I wanted to feel each hill and bump of the earthly connection between London and Istanbul… but also to allow for some time-travelling between the world of now and the world of then which Constantinople represents for me. It takes three days and several hundred pounds to go by train, though, so BA flight 678 it is.

I’ve wanted to go there since I was 12. That’s when I first read about the city and got bewitched by it in Henry Treece’s brilliant A Viking Saga, in which the Viking heroes end up in Miklagard – how many names can one city have?

But since then, I’ve grown to love Byzantium because Eastern Orthodoxy fed me spiritually for years, throughout the 1990s and into the 2000s. I loved and drew on the alluring mysticism of icons and Eastern liturgy, and Byzantium was the geographical centre of that world. It was there that one of the most beautiful icons of all, the Virgin of Vladimir (seen above), was created and then sent into pagan Russia to help form Russian Orthodox spirituality.

I’m looking forward to standing in Hagia Sophia, the Church of the Holy Wisdom, and paying my respects. The church, built in the faraway 6th century, is more than half a millennium older than Chartres Cathedral. But there’s also a smaller church near the city walls with a fresco of the resurrection which I’m anticipating will be a demanding spiritual encounter.

Byzantium is a place of meeting and conflict between Christianity and Islam – just the conflicting names of the place tell their own story. Someone today on Twitter told me, ‘Don’t call it Constantinople, the Turks get very pissy about that.’ So I’m hoping also to get a better understanding of this place where the tectonic plates of faith get frictive with each other.

Comment (0) |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

God indicates that Twitter is cool

Posted on 17 September 2010, 16:44

A new sign has been vouchsafed to us in the form of a dove-shaped cloud in the sky. John Gray, a former RAF photographer (and former Catholic), spotted the cloud from his back garden on Wednesday night, the eve of the Pope arriving in Britain. His interpretation? ‘When I saw it I thought that it probably signifies what the Pope needs – a bit of peace and happiness.’

However, with all due respect to Mr Gray, it’s surely clear that the cloud is not any old dove, but the Twitter logo. God is saying to this generation: ‘Twitter is my fave social media. Go forth and tweet.’ The sign must also be confirmation that the Almighty is pleased with the new version of Twitter, which is being rolled out in the next few days.

Comment (0) |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Heaven’s comedian

Posted on 26 August 2010, 4:47

I hadn’t heard of him before today, and alongside St Simeon the Holy Fool (who is the patron saint of Ship of Fools), I think St Genesius the Comedian is a good addition to the house of unlikely saints. His martyrdom is related in the medieval Acts of the Saints and it’s highly likely to be pure legend, but it’s an interesting story, nevertheless.

The story of Genesius is set in the time of the Roman Emperor Diocletian, who was behind the most severe of all the persecutions of Christians at the beginning of the 4th century AD. Genesius was the leader of a theatrical troupe, and hearing that the emperor was coming to town, prepared a comic satire against the Christians for his entertainment.

In the comedy, actors playing the part of a priest and an exorcist came to mock-baptise Genesius, but as he was washed with water, he had a vision. He saw a company of angels who read out his sins from a book, and then washed the book clean, turning his stage baptism into a real one. Genesius was converted on the spot and when he began to preach to the audience, the emperor, who had been laughing at the comedy, became enraged. Genesius was beaten and then killed.

The early church was mostly hostile to the theatre and circuses, and the story of Genesius can be seen as an attack on the theatre; but in a curious way it’s redemptive, suggesting that even the mockery of faith can lead to the discovery of faith. St Genesius remains an important spiritual champion for actors, and one set of prayers I found today calls him ‘heaven’s comedian’. The modern icon shown above has the masks of comedy and tragedy tucked inside his cloak.

Here’s a good article which includes a version of his story.

Comment (0) |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

The first icons?

Posted on 11 July 2010, 23:22

Last month, a burial chamber in Rome from 17 centuries ago, part of the Catacomb of St Thecla, was opened to the world’s press after its walls had been scraped clean by lasers. The lasers have uncovered an amazing array of wall paintings showing biblical scenes, but best of all is the chamber’s colourful ceiling, with bold geometric patterns.

At the centre of the ceiling is a smiling Christ carrying a lamb on his shoulders, while the four corners have medallions containing portraits of the apostles Peter, Andrew, John and Paul.

Because the chamber is from the late 4th century, these are the oldest known images of John and Andrew, and that was the detail which made headlines in the media. But more significant than that is the format of the painting, with the four apostles surrounding Jesus. This suggests they were being venerated in some way, which makes them the earliest example of Christian icons – images used in prayer and worship – we know about.

Other early images of the apostles show them as actors in scenes from the four Gospels, but here they appear in the stillness of portraits. They turn to look out at us directly to encourage and hear our prayers. Their position on the ceiling suggests they are looking down from heaven. These images give us a glimpse into a very early moment in the development of icons, about 350 years after the death of Jesus.

It’s especially enjoyable to recognise the image of St Paul (shown above), who looks exactly as he does in later icons. There are earlier depictions of Paul (although not many) which have this same look, which was taken from a description in a 2nd century book, The Acts of Paul.

In the opening of the book, Paul is spotted in the street in the Roman town of Iconium, and described as ‘a man small of stature, with a bald head and crooked legs, in a good state of body, with eyebrows meeting and nose somewhat hooked, full of friendliness; for now he appeared like a man, and now he had the face of an angel.’

Comment (0) |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

In the habitat of icons

Posted on 01 July 2010, 5:39

The Temple Gallery is in a small and perfect parade of upmarket shops just crying out to be turned into a film location for a murder mystery. It’s in Clarendon Cross, lost among the handsome houses to the west of Notting Hill, and just a few steps away from Julie’s, the rambling and informally grand restaurant and bar.

The gallery has been running since 1959 and is named after the affable and highly knowledgable Richard Temple, for whom Orthodox icons are a lifelong passion and pursuit. He holds icon exhibitions at the gallery every summer and Christmas, and I visited the latest one (on until 12 July) at the weekend.

The gallery has kept its small shop feel, and you follow the icons through a succession of snug rooms on the ground floor and down into the basement. Since most of the works were made for display in the home, it does feel like they are in their natural habitat, giving the exhibition a homely and personal atmosphere.

The jewel of the show is the Madre dela Consolazione (a Madonna and child) from 15th century Crete, painted after the fall of Constantinople to the Turks and at a time when the Orthodox vision of how icons should be painted was being diluted by influences from the Catholic West. It’s therefore not my favourite sort of icon, but this is a majestic and imposing masterpiece.

Hung right next to it is the image which took my breath away: a Russian icon of Saints Nicholas and Leonti of Rostov. This icon is painted in such subdued, earthy, chocolaty colours, you just have to stop in front of it for the pleasure of seeing how beautifully it has been made. While the Madonna and child are seen in the hard bright light of Crete, saints Nick and Leonti are in the dim and tranquil colours of the north Russian forest, which is probably where the ochre and brown pigments actually came from.

I’ve often found the restrained colours of Russian icons a more beguiling invitation to pondering and prayer than the brash colours of their Greek cousins, and that’s certainly the case in this image.

Icons are given so little exhibition space in London that it’s an opportunity not to be missed to see this summer show. Alternatively, all the icons can be viewed online at the Temple Gallery website, where generously sized photographs are teamed with expert notes. The gallery was conceived as a centre for the study of icons as well as an exhibition space, and the online show fulfils that aim admirably.

Comment (1) |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|