|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Category: art

|

|

|

|

Holy Saturday

Posted on 30 March 2013, 21:46

Holy Saturday is the forgotten middle day of Easter. Where Good Friday and Easter Sunday are full of action (and church services), Saturday is simply the day when Jesus lay dead in the tomb. It is the eye of the hurricane of Easter.

I was powerfully drawn to this 12th century Greek icon for Holy Saturday (above) when I first saw it in the 1980s. Greek icons normally show Jesus as a powerful, commanding figure. Even icons of the crucifixion are entitled, ‘The King of Glory’. But here we see Jesus broken in the ultimate weakness of death.

The image puts us in the tomb with Jesus. And there we see suffering. This dead face is set in a frown. There are dark shadows under the eyes – the shadow under the left eye is like a bruise. The shoulders are hunched and tense, while the arms are limp and useless. The body of Jesus looks like a media image of a torture victim.

But we also see vulnerability here. Jesus has the mouth of a sleeping child, with the lower lip sucked under the top lip, for comfort. The head is bent as if in sleep. We see the openness of Jesus to suffering and death. We see God made poor, weak and helpless. I don’t think there is any other image which shows this with such depth of emotion and insight.

The icon shows us the beauty of Christ in his obedience to the will of God, at vast cost to himself, and also in his unconditional love for us. Because it is for us, for our sake, that he is here like this. And this creates longing. The Orthodox liturgy for Holy Saturday, the day when this icon was carried through the streets, has a prayer which gives words to longing.

‘O faithful, come, let us behold our Life laid in a tomb to give life to those who dwell in tombs. Come, let us behold him in his sleep and cry out to him with the voice of the prophets: You are like a lion. Who shall arouse you, O King? Rise by your own power, O you who have given yourself up for us, O Lover of mankind.’

Comment (1) |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

In Seven Days…

Posted on 18 February 2013, 1:26

A feature I wrote on the artist Nicola Green was published in the Church Times this week. I visited Nicola, a portrait artist, at her north London studio a couple of weeks ago and had a fascinating conversation with her about her project In Seven Days… in which she shadowed Barack Obama during his 2008 campaign to become president. She created seven icon-like works out of the experience.

No one has ever been artist in residence to a US presidential campaign before. Nicola visited the campaign six times over the course of several months. She sat in the front row and sketched as Obama made speeches; she talked to staffers behind the scenes, citizens in the crowds and Obama himself at key moments in the campaign; and she collected magazines and ephemera along the way.

Throughout, Nicola took on a trappist-like vow of silence about the project, talking only to her husband and parents about it all. Back in her studio, after Obama’s inauguration in 2009, she distilled all those sketches, photographs and conversations to produce images which reflect on the impossibility of what Obama set out to do.

‘In Seven Days…’ is current on show at the Walker Art Gallery in Liverpool.

I was especially struck by the first of the images, ‘The First Day, Light’ (seen above). It came from the moment in August 2008 when a crowd of 70,000 people was waiting in a giant stadium in Denver, Colorado, to see Barack Obama stride out onto the Democratic Convention platform and accept his party’s nomination as candidate for the US Presidency. In the moments before he arrived, the crowd, electrified by the significance of the event, erupted into a Mexican wave, with everyone leaping to their feet.

Nicola told me that she leapt up with them, but commendably, she kept her artist’s head in the intoxicating atmosphere. In the speeches leading up to this moment she had sketched the expressive hands of people around her. And as the wave cascaded through the crowd she photographed the hands as they waved, pointed or reached up in expressions of joy and praise.

Says Nicola: ‘The seven hands represent the 70,000 people, but also the fact that everybody around the world was watching this story. It was also a clock and about the timing of this moment.’

For more, see the Church Times piece (you have to subscribe to see it online). Or visit Nicola Green’s website. I’m hoping to talk to her again sometime when her next project is completed.

Comment (0) |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Born again fish?

Posted on 16 November 2012, 8:20

I went to Croatia a few weeks ago and visited the seaside town of Poreč (a name charmingly pronounced like ‘porridge’, but with a ‘ch’ sound at the end), which is home to a very ancient Christian church. Still standing is a modest, 6th century Roman basilica, which is quite plain inside except when you look to the front and see beautiful, glowing mosaics filling the semi-dome of the apse. In the centre of the mosaic is an image of Mary holding Jesus in her lap, with a smiling angel on either side. It is said to be the oldest surviving image of Mary in a western basilica.

But outside are even more wonders, because right next door to the basilica is the footprint of an earlier, 4th century church, which astonishingly still has its fine mosaic floor, open to the sky. The sea laps the shoreline less than 50 metres away.

Guard railings prevent you from actually walking on the floor (thank goodness), but you can easily see the weather-stained geometric shapes, flowers and foliage which fill the space. But there’s something else in the floor, and it’s a surprise. In the midst of all the patterns is a solitary fish. It’s rather randomly placed, top right in a big square that’s been sub-divided into a checkerboard of nine squares, three to a side. It’s as if a fish fell out of a shopping bag onto a highly patterned Persian rug and was left there for no particular reason.

I knew the basilica had this fish mosaic, and it was the main reason I wanted to visit Poreč in the first place. The fish is one of the earliest symbols of the Christian faith, dating right back to the times when Christians were persecuted and needed codes and ciphers to communicate safely with each other.

The word for ‘fish’ is ichthus in Greek, and the individual Greek letters can each be used to start a word which then forms the sentence, ‘Jesus Christ, Son of God, Saviour’. That’s how you turn an ordinary fish into a discreet little confession of faith. And of course this clever symbol has stood the test of time. You can buy cute versions of the same fish symbol and stick them on the back of your car to annoy the driver behind.

I was especially looking forward to seeing the fish of Poreč, because it was created in the same tumultuous century as the final persecution of the Christians, which was followed by the adoption of Christianity as the official religion of Rome. For that reason, this particular fish was made by men within living memory of the persecuted church, which gave birth to the symbol.

But two things took me by surprise. First, inside the basilica’s museum, you can see a copy of the mosaic close up. And I just wasn’t expecting to see a fish which looked so aggressive, with spines and needle-sharp teeth (see the picture above, or a bigger version here). The fish, after all, is meant to signify Christ himself. My wife Roey voiced what I was thinking: ‘That can’t be the ichthus fish because it looks so horrible!’

This made me think that maybe the leaflet we’d picked up at the ticket office, which described the mosaic as a ‘Fish – Christian symbol’, might be wrong. It could be that the fish was just a fish, part of the decoration of this ancient Christian building, which also features fruit and vines, flowers and leaves, without each detail being deeply symbolic.

The second surprise, though, was seeing the fish in the actual mosaic pavement, where it had been placed 17 centuries earlier. It is the only animal in the whole floor, and there it is, at the very front of the church. It simply stands out as something exceptional and eye-catching. As something significant.

Maybe it’s just there because the merchant who paid for this stretch of mosaic was in the fish trade and wanted to be remembered. But the symbol had such resonance for the newly-liberated Christian community that it’s hard to imagine it landed there on a tradesman’s whim, stripped of its cherished history and hidden meaning.

In a fishing town like Poreč, the makers of ancient mosaics knew what fish looked like, and they drew them as they saw them in the market, teeth and all. The craftsman who made this fish also depicted the gills like a wound in the fish’s side, using dark red stones.

I think this is a genuine ichthus – unlike the Disneyfied version seen today on a thousand bumper stickers.

See my Flickr gallery of the Euphrasian Basilica, Poreč.

Comment (2) |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

My friend Paul Clowney

Posted on 17 April 2012, 6:29

Paul Clowney, who died on Good Friday, was a friend I loved and respected for most of my adult life, and so the thought of him no longer being here is as nonsensical and perplexing as someone saying the rain’s going backwards. Several days since getting the news, I still can’t take it in. How is it possible for Paul to be gone? I find death more astoundingly opaque as I get older, when I thought it would get more transparent.

A friend texted me on Good Friday afternoon, just hours after Paul died, to remind me of a meal we shared where Paul arrived, took in the smell of coriander coming from the kitchen and said, ‘Ah… coriander. Reminds me of Vietnam.’ I can hear him saying it, in that cool and calming American accent of his.

That story reacquaints me with one of the things I always appreciated about Paul, that he was from elsewhere, culturally. From Vietnam, as a photographer with Richard Nixon’s army; from Philadelphia, where his father, Ed Clowney, was professor in theology; from Amsterdam where he studied and met his wife Tessa; from Francis Schaeffer and Hans Rookmaaker and ways of thinking about art and faith that were unfamiliar and highly creative.

Outstandingly for me, Paul was a maker. He knew how to make things that worked and fix them when they didn’t. He was a person who either understood or was so curious about objects that they would eventually reveal their secrets to him. If you were ever going to be stranded on a Pacific island with nothing to eat but coconuts, you would surely want Paul with you, because he would put Robinson Crusoe to shame for inventiveness.

Paul is the only person I know who would bring a set of chisels with him on a weekend break to Lyme Regis. He used them to crack open rocks on Lyme’s Jurassic beach and expose fossils which last saw the light of the sun 180 million years ago. He was a magician of that sort of thing.

Roey and I first met Paul and Tessa in 1978 when they invited us to one of their ‘Art at Home’ exhibitions in Ealing. They turned their home into a temporary gallery for an art show by painting the walls, removing all the internal doors and hanging pictures. It was a characteristically playful and effective concept of them both. We had just got engaged and were looking for somewhere to live, and they beguiled us into becoming their Ealing neighbours.

I can still see them both in that house’s conservatory, talking with friends under the leaves of their luxuriant vine while the music of Kate and Anna McGarrigle filled the house. And I can see Paul, with his long hair and dense moustache, sitting at the scoring end of a shuffleboard, offering encouragement and advice as various friends sent the pucks flying up the board.

I’ll always remember the beautifully calm and rational way he prayed grace before meals – prayers which were practical and simple, but borne out of a deep faith in the God who is there. Prayers which were a blessing not just of the food and wine on the table, but of us too.

I sit here now, writing these words after midnight, before I go to bed. I know Paul did this self same thing many, many times, because I used to call him at his agency, The Clearing House, after midnight when I had a technical problem I couldn’t fix, and he would simply say, ‘Come on over.’

And I think: All Paul’s deadlines, all his to-do lists and client relationships, and all his after-midnight tasks are now done. His great project is completed. As it says: ‘Blessed are those who die in the Lord, for they rest from their labours.’

And it also says this: ‘All you who, in life, have taken on you the cross as a yoke, and have followed Me through faith, draw near: Enjoy the honours and crowns which I have prepared for you.’

That is how I shall always think of Paul. My loved and honoured elder brother in faith.

Photo: Hans Clausen

Comment (8) |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Devotion by design

Posted on 31 July 2011, 23:28

I skipped church this morning and went to see the National Gallery’s Devotion by Design exhibition instead. It wasn’t a bad swop, as the exhibition is about Italian altarpieces from before 1500, and these amazing creations were presented in darkened rooms with the sound of liturgy and music in the background… all very atmospheric.

The exhibition, which runs until 2 October, is quite ‘how to’. That is, it’s very interested in how these multi-image pieces were constructed, allowing you to poke around behind two huge altarpieces to see the carpentry beneath their glittering, golden faces, and the surgery they have endured over the centuries.

One room explains how the people who commissioned and paid for the altarpieces imposed their own choice of saints and sacred stories on the artist. If there was more than one institution commissioning the piece, then the haggling over the cast list of who should appear in the picture could go on for a very long time.

What I missed was a good explanation of the role of altarpieces in church worship, or their impact on the ordinary worshipper. After all, in the age before television and giant advertising images, these pictures must surely have had huge impact, especially as they were positioned so you were looking right at them during the high point of the eucharist. The hyper-realism of some of the painting also draws you into an encounter, despite yourself, with the saints shown there.

I leafed through the exhibition catalogue in the shop afterwards, and it had good material on the place of altarpieces in the church’s liturgy, so it’s a shame that wasn’t reflected in the exhibition itself.

That said, Devotion by Design is thoughtful and intriguing, especially if you’re interested in the construction, technique, negotiation and contracts that underlie these powerful images used in Christian worship.

Comment (1) |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Battle of the Christs

Posted on 15 June 2011, 6:44

A new titanic Jesus statue seems to be going up every year. Last November saw a local Catholic priest realize his dream to put up the world’s tallest Christ in Swiebodzin, Poland, and this year it’s the turn of the President of Peru, who has fast-tracked a gargantuan Saviour for the city of Lima.

The statue, which will face the Pacific, is to be unveiled this month, and will ‘bless Peru and protect Lima,’ according to the President.

There’s some confusion, though, about whether this will be the tallest Jesus of them all. Media reports say the Lima statue will be 37m tall, but that appears to include a 15m pedastal, which reduces our Lord himself to a mere 22m.

Excluding their pedastals, here’s how the world’s other giant Jesi stack up…

Christ the King, Swiebodzin: 36m

Cristo de la Concordia, Cochabamba: 34.2m

Christ the Redeemer, Rio de Janeiro: 30m

Christ Blessing, Manado: 30m

Hopefully more news soon on the thrilling question of who has the biggest Jesus of them all, a revelation which is possibly of more interest to male readers.

Comment (4) |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Treasures of heaven

Posted on 07 April 2011, 2:23

I went yesterday to the British Museum’s press launch for their major summer exhibition, Treasures of Heaven. The show promises to shine light on one of the most curious – not to say bizarre – aspects of the Christian faith: the devotion shown to relics.

Statues of saints and their relics were smashed or forcibly removed from British churches in the 16th century Reformation, and might seem like an obscure historical footnote now. But as Neil MacGregor, director of the BM, pointed out at the launch, relics were hugely significant objects in medieval Europe, bringing power, prestige and wealth to towns and cities, especially if they became the destination of pilgrims.

Talking about one of the exhibition’s star relics, a thorn said to be from Christ’s crown of thorns and housed in a kitschy gold reliquary (seen above), MacGregor quipped that ‘at the second coming, Christ would make a point of coming to Paris to collect his thorn.’ It was this kind of belief about relics which put medieval cities on the map.

The exhibition will bring together relics, reliquaries, manuscripts, prints and pilgrim badges from more than 40 institutions around the world, including the private chapel of the popes in the Vatican. The chapel is sending the Mandylion of Edessa (or a 5th century copy of it, at any rate) which is rarely seen in public, so that will be an event in itself.

I was told that staff at the museum are expecting some visitors to venerate the relics during the show.

Karen Armstrong, also at the launch, talked about the difficulty of relics for post-Reformation people. In fact, she said they were possibly ‘rebarbative’ (repellent) in modern culture, not a word you hear every day. The pilgrims who travelled to venerate the bones of saints and martyrs ‘confronted death but also discovered something which transcended death.’

She recalled the death of Princess Diana and how people lit candles and heaped up bouquets of flowers on the streets, ‘so that London seemed like India because of the smell of rotting vegetation!’ The cult of relics and the cult of celebrity may be a lot closer than we think.

Treasures of Heaven will run from 23 June to 9 October and tickets are now on sale.

Comment (0) |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

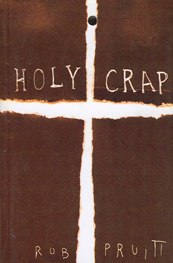

Holy Crap

Posted on 20 January 2011, 0:33

In Koenig Books on Charing Cross Road yesterday, my eye fell on Holy Crap. It’s a paperback printed on cheap paper, with gold spray-painted edges, like an old-fashioned Bible, and a hole punched through it so you can hang it up in your toilet. And inside are hundreds of black and white pictures of US church signboards, which have long been the home of smug comments, pious puns, and sacred sayings which unexpectedly turn out to have a second life as jokes about bonking…

The best vitamin for a Christian is B1

The most powerful position is on your knees

You give God the credit, now give God the cash

Family altar or Satan will alter your family

There can’t nobody do me like Jesus

The book is a project by New York artist Rob Pruitt, whose work often uses comedy to comment on mass and trash culture – such as his 1998 show, Cocaine Buffet, which consisted of a very long line of coke on a mirror on the floor of an artist’s studio. All of which was obligingly hoovered up by the show’s visitors.

In the intro to Holy Crap, Pruitt says, ‘I love multitasking, like driving and having a religious experience at the same time.’ Which is funny, but I’m more interested in what he said in a press release for the book’s launch last year: ‘We had a discussion about the Church, the Church signs in the US along the streets, about their poetry, about seduction, repression and basement tapes. The fact that these Church signs make you laugh, but that the Church isn’t funny, not the Catholic Church, none of them, no.’

We’ve been collecting church signs and religious gadgets on Ship of Fools for years, mostly playing to the comedy aspect, but this is a good reminder of the unfunny heart which lies behind it all. The humour is provided by the ironic take of Ship of Fools and the viewer’s enjoyment of that, rather than by the people producing the church signs or the holy hardware, whose intent is serious.

Elsewhere, Rob Pruitt describes his mixed feelings towards the cultural excess he depicts, which sounds like it’s coming out of the grey area satirists work in: ‘On the one hand I want to celebrate it, because it’s who we are, and on the other hand I want to condemn it. I think it’s always like a ping-pong match for me.’

Comment (1) |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Heaven and hell in a country church

Posted on 09 October 2010, 4:47

Flying to Byzantium: Entry 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | Photos

Istanbul, Sunday: Tali and I emerged from the depths of Hagia Sophia and went to sit in the open air café in the gardens outside for a calming cup of coffee and cigarette after all that religious intensity. I don’t normally smoke, but it was definitely time for some nicotine-assisted reflection.

Meanwhile, great dollops of beautiful warm sunshine were being generously served up on Istanbul, and after a quick visit to a cash machine, followed by a stroll among the underground pillars of the Byzantine cistern of Yerebatan, which is across the road from Hagia Sophia, we jumped into a yellow taxi.

‘Can you take us to the Chora Church?’ I asked our small, moustachioed driver. ‘Yes,’ he replied. And then sped off in the opposite direction to the church.

There followed some back seat angsting over whether we were being taken for a ride, until our driver explained that the police had closed the obvious routes because the town was choked with tourists. We drove around the Saray point and up the Golden Horn, with more than enough to look at on the way: towering, historic mosques, noisy, colourful markets, people enjoying lunch on the street, sticking their faces into chicken kebab wraps, ferries roaring out into the lively waters around the Galata Bridge.

Ten minutes later and we swept left along a broad road and were suddenly alongside the massive medieval walls of Constantinople, looking at them from the outside, just as the Ottoman attack troops had done before the city fell to them in 1453. And then left again, through a great breach in the walls, and we dropped down a narrow street to St Saviour’s, the Chora Church.

One of the meanings of chora is ‘country’, and as this whole area was rural even into the 20th century, the Chora Church is basically the ‘country church’. Which sounds very sleepy to English ears – and there is something country in feel about this place. It has a shady, walled garden at the back, and over the wall I could hear a children’s playground. But far from being just another country church, St Saviour in Chora is a jewel of Byzantine art: rebuilt in the 11th century and then decorated with the most stunning mosaics and wall paintings during a six-year makeover in the 14th century.

If that sounds a bit serious, then stepping inside makes you realise it’s entertaining, too, because the scenes covering the walls and ceilings of this lovely building are full of incidental detail: the water jars being topped up at the wedding feast of Cana; children playing on the edges of the crowd in the feeding of the 5,000; an angel carrying a giant scroll with the sun and moon rolled up in it at the last judgment. This is medieval television and the glass pixels in the mosaics are tiny enough to make it hi-def.

As you walk into the church, you pass beneath a monumental head and shoulders of a fierce-looking Christ. This is titled, ‘Jesus Christ, the chora (land) of the living’. So you enter under a theological pun which plays with the church’s name and the words of Psalm 27: ‘I am still confident of this: I will see the goodness of the Lord in the land of the living.’

But the face remains powerful. In her book, The Irrational Season, Madeleine L’Engle describes visiting the Chora Church and seeing this image of Christ. She says, ‘I knew that if this man had turned such a look on me and told me to take up my bed and walk, I would not have dared not to obey. And whatever he told me to do, I would have been able to do.’

Like Howard Carter at the opening of Tutankhamen’s tomb, we saw ‘wonderful things’ as we walked around, but I was here mainly for one wonderful thing: a fresco I had seen long ago in a book and which has lodged in my heart and head ever since. I saved it for last. It’s in the church’s burial chapel, painted inside the half dome at the east end, filling the whole of that curved space.

Standing dead centre beneath the icon, Tali and I looked up and became for the moment its intended viewers. Its title is Anastasis, ‘The Resurrection’, and in it the most alive Christ you’ve ever seen strides through hell, seizes Adam and Eve by the wrists – just as you’d grab the wrist of a difficult child – and pulls them bodily from their tombs. Beneath his feet are the trashed gates of hell, and below that is Satan, bound like a slave and surrounded by broken locks, chains, jailer’s keys and other small debris from the infernal workshops.

But it is Jesus who commands the scene, and your attention. I’ve never seen him painted this way. Byzantine icons are famously formal and still, with the look of people who have been told to hold a pose and not move. But this Jesus is caught in swift and decisive movement. He captures the vigorous words of the Orthodox Easter liturgy…

Christ is risen from the dead,

trampling down death by death,

and to those in the tombs he has given life.

This is so far from the seven-stone weakling Christ I saw pinned up in Sunday school in the 1960s, and so far from the bleeding victim Christ of Catholic statues which weep, that it took my breath away when I first saw it. Like reading Mark’s Gospel, it made me want to follow Jesus then… and now.

Did Jesus rise from the dead? I don’t know. What I do know is that I’d trade just a glimpse of this image for a hundred evangelical books which try to argue ‘the case for the resurrection’ like a whodunit. The Christ shown here powerfully makes me want to believe, and my unbelief can go hang.

Having said all that, I stood still under the image: absorbed, gazing, listening in the few minutes of my life I was there. Madeleine L’Engle says she trembled with joy as she stood on the same spot. For me it was wonder freed from emotion, which I hadn’t expected.

I don’t know if I’ll ever be here again. But I live in the glow of it. I hope for the life and transformation promised here. I hope to be in the land of the living Christ.

Comment (3) |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

When low-grade offence offends

Posted on 14 July 2010, 5:19

The past week has been a pretty good time for images intended to shock religious people – and religious people have been performing their expected role faithfully.

The publishers of the Portuguese edition of Playboy put Jesus on this month’s cover (above, with black strip to protect the identity of the female model, ha ha), and were sacked by Playboy USA for their trouble. Presumably, Hugh Hefner is worried that the image will damage sales of the venerable porn mag among fundamentalists, which must be considerable.

And in Moscow, the curators of Forbidden Art, an exhibition of satirical art pieces which other galleries refused, were fined 350,000 roubles (that’s £7,500) after a two year trial supported by right-wing groups connected to the Russian Orthodox Church. The exhibition included a crucifixion with Lenin’s head replacing that of Jesus, an icon of the Mother and Child filled with caviar, and Jesus next to the golden arches of McDonalds with the slogan, ‘This is my body’.

Not great art, but also not great offence. And anyway, when did Christians start thinking they had the right to stop people offending them, or for ‘blasphemy’ to be treated as a criminal offence, instead of using events like this as a trigger to discussion about faith? Probably as far back as AD 313, when Constantine converted and the Roman Empire became ‘Christian’.

It’s alarming to see the Russian Orthodox Church with real power in its hands again, and it’s a reminder of how ugly church can be. To see some of the Forbidden Art exhibits online, visit the Russia! blog.

Comment (1) |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

The first icons?

Posted on 11 July 2010, 23:22

Last month, a burial chamber in Rome from 17 centuries ago, part of the Catacomb of St Thecla, was opened to the world’s press after its walls had been scraped clean by lasers. The lasers have uncovered an amazing array of wall paintings showing biblical scenes, but best of all is the chamber’s colourful ceiling, with bold geometric patterns.

At the centre of the ceiling is a smiling Christ carrying a lamb on his shoulders, while the four corners have medallions containing portraits of the apostles Peter, Andrew, John and Paul.

Because the chamber is from the late 4th century, these are the oldest known images of John and Andrew, and that was the detail which made headlines in the media. But more significant than that is the format of the painting, with the four apostles surrounding Jesus. This suggests they were being venerated in some way, which makes them the earliest example of Christian icons – images used in prayer and worship – we know about.

Other early images of the apostles show them as actors in scenes from the four Gospels, but here they appear in the stillness of portraits. They turn to look out at us directly to encourage and hear our prayers. Their position on the ceiling suggests they are looking down from heaven. These images give us a glimpse into a very early moment in the development of icons, about 350 years after the death of Jesus.

It’s especially enjoyable to recognise the image of St Paul (shown above), who looks exactly as he does in later icons. There are earlier depictions of Paul (although not many) which have this same look, which was taken from a description in a 2nd century book, The Acts of Paul.

In the opening of the book, Paul is spotted in the street in the Roman town of Iconium, and described as ‘a man small of stature, with a bald head and crooked legs, in a good state of body, with eyebrows meeting and nose somewhat hooked, full of friendliness; for now he appeared like a man, and now he had the face of an angel.’

Comment (0) |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

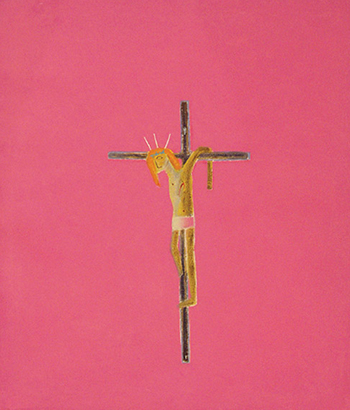

Calvary canis

Posted on 02 July 2010, 13:37

Meanwhile, back in the Methodist art exhibition at Wallspace, I forgot to mention the most curious detail of the show, in Pink Crucifixion, a print by Craigie Aitchison (above). Looking at the lonely scene, I was told it once included a dog standing at the foot of the cross. However, the dog lacked an eye, and when the print went to press, the printmaker added one; which didn’t go down well with the artist, who ordered the dog out of the scene altogether. Fido can still be seen by the faithful, though, in ghostly outline (below). Reminds me of Schrödinger’s Cat.

Comment (0) |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

In the habitat of icons

Posted on 01 July 2010, 5:39

The Temple Gallery is in a small and perfect parade of upmarket shops just crying out to be turned into a film location for a murder mystery. It’s in Clarendon Cross, lost among the handsome houses to the west of Notting Hill, and just a few steps away from Julie’s, the rambling and informally grand restaurant and bar.

The gallery has been running since 1959 and is named after the affable and highly knowledgable Richard Temple, for whom Orthodox icons are a lifelong passion and pursuit. He holds icon exhibitions at the gallery every summer and Christmas, and I visited the latest one (on until 12 July) at the weekend.

The gallery has kept its small shop feel, and you follow the icons through a succession of snug rooms on the ground floor and down into the basement. Since most of the works were made for display in the home, it does feel like they are in their natural habitat, giving the exhibition a homely and personal atmosphere.

The jewel of the show is the Madre dela Consolazione (a Madonna and child) from 15th century Crete, painted after the fall of Constantinople to the Turks and at a time when the Orthodox vision of how icons should be painted was being diluted by influences from the Catholic West. It’s therefore not my favourite sort of icon, but this is a majestic and imposing masterpiece.

Hung right next to it is the image which took my breath away: a Russian icon of Saints Nicholas and Leonti of Rostov. This icon is painted in such subdued, earthy, chocolaty colours, you just have to stop in front of it for the pleasure of seeing how beautifully it has been made. While the Madonna and child are seen in the hard bright light of Crete, saints Nick and Leonti are in the dim and tranquil colours of the north Russian forest, which is probably where the ochre and brown pigments actually came from.

I’ve often found the restrained colours of Russian icons a more beguiling invitation to pondering and prayer than the brash colours of their Greek cousins, and that’s certainly the case in this image.

Icons are given so little exhibition space in London that it’s an opportunity not to be missed to see this summer show. Alternatively, all the icons can be viewed online at the Temple Gallery website, where generously sized photographs are teamed with expert notes. The gallery was conceived as a centre for the study of icons as well as an exhibition space, and the online show fulfils that aim admirably.

Comment (1) |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

My art was strangely warmed

Posted on 23 June 2010, 19:14

A new exhibition opens in London today featuring highlights and new works from the Methodist collection of modern and contemporary art. I’ve never seen the Methodists and modern art in the same sentence before now, and one friend suggested the two go together ‘like Evangelicals and literature’. So finding out about this collection is an unexpected surprise.

The collection, which includes more than 40 works, dates back to the early 60s when Methodist art collector John Gibbs started buying works for the church after noticing that many modern artists were working with biblical themes. Bits of the collection are frequently on tour in churches around the country. See here for the website of the collection.

The show is at Wallspace – ‘a spiritual home for visual art’ in the City church of All Hallows on the Wall – from now until 16 July. It includes paintings and prints from the 20th and 21st centuries, and all of them look perfectly at home in this 18th century sanctuary.

From the older school, I was most struck by Graham Sutherland’s domestic icon of The deposition, with its reversed perspectives and an ochre sky standing in for the gold leaf of icons; and also by The crucifixion of Francis N Souza, with its expressive hands and midnight blue sky.

Among the more recent works, Mark Cazalet’s Fool of God brings the colours of bloody death into a night-time garden. I’ve seen Jyoti Sahi’s The Dalit Madonna before, in a small jpeg on the Net, but the sheer size and presence of the actual painting are something to experience.

The collection also commissions contemporary art, and a small example of that caught my eye before I left: Clive Hicks-Jenkins’ study for Woman Taken in Adultery (which I took a snap of, see above). I was surprised by the fear and degradation of the image and realised those themes rarely come out of the story in John’s Gospel. I hope Hicks-Jenkins keeps that oppressive feeling in his final version of the work for the collection.

Comment (1) |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Picture perfect

Posted on 20 June 2010, 16:59

Went into London on Friday to see the Royal Academy summer show: 14 rooms filled with beautiful, intriguing, baffling and unexpected art. I didn’t see anyone else laughing at it, but in the corner of one of the rooms, above an exit door, the picture hangers had placed Work 100 to perfectly align with the exit sign. The print, Ladies in Waiting by Tom Karen, shows three symbol women waiting in line to use a female loo, and judging by the red dots, 38 copies of the £110 work had already been sold. No red dot next to the exit sign, though.

Comment (1) |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Mocking Muhammad

Posted on 22 May 2010, 18:07

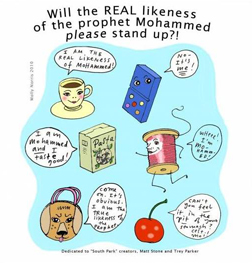

It’s hard to know what was going on in the mind of Molly Norris, a previously little-known cartoonist in Seattle, who casually proposed celebrating 20 May as Everybody Draw Mohammed Day on her blog back in April (complete with her own cartoon, above). Presumably she’s never attacked a hornet’s nest with a large stick. Her post was a protest at Comedy Central’s decision to edit sections of an episode of South Park showing Muhammad dressed in a bear costume.

Norris’s proposal sparked a Facebook group campaigning for the event, under the banner of freedom of speech, which was quickly countered by other Facebook groups attacking it. Under a rain of angry emails, Norris withdrew her proposal, but by then the juggernaut was rolling. ‘It’s been horrible,’ she said in an interview. ‘I’m just trying to breathe and get through it.’

When I checked on the morning of 20 May, the Facebook group had 77,000 members and 6,000 images, most of them of the sort that would make the calmest imam delve into his filing cabinet for the section called fatwa. Looking at the brutality of the visual humour, I was reminded of a comment in Boccaccio’s The Decameron, where one of the storytellers says that ‘the nature of wit is such that its bite must be like that of a sheep rather than of a dog, for if it were to bite the listener like a dog, it would no longer be wit but abuse.’

By that point, Pakistan had blocked the whole of Facebook, and followed that up by blocking YouTube, which was carrying video contributions to the campaign. Later in the day, after the group soared past 100,000 members, Facebook removed it, presumably under pressure from protesters.

Out and out mockery of people’s deeply held beliefs has a long and undistinguished history. One of the earliest images we have of the crucifixion is a piece of graffiti scrawled on a wall in Rome showing Jesus with the head of a donkey. That public attack on the Christian faith is mild compared with the savagery in the images collected on Facebook, and it’s surprising that the event hasn’t roused the mass demonstrations which followed the publication in 2005 of the infamous Muhammad cartoons in Denmark’s Jyllands-Posten. Five people died then in the riots in Pakistan.

All religions, but especially the ones in the monotheism brand, need to find ways to take the piss out of themselves, since they have always been so brilliant at taking themselves too seriously. Religions with no sense of humour play especially badly in the western world where irony is in the very air we breathe. If religions can’t or won’t do this, they open themselves to cultural attack, and social media now make this possible in a fast-moving and extremely uninhibited way.

It takes just a few minutes to make an image trashing someone else’s deeply held beliefs, adding shock in the form of bestiality, paedophilia or whatever else comes to hand, and then posting it from the comfort of your laptop. But added to that is the high of performing on the Facebook stage, of knowing that my joke or insult will succeed in amusing or enraging thousands of others.

We’re suddenly living in the age of mass satire, where poorly-considered but deadly insults, barely clothed in humour, are published instantly and made available to a global audience. In the social furnace of Facebook, such rapidly accumulating insults create the visceral mood and momentum of a mob. Reading the wall comments of the ‘Everybody Draw Muhammad Day’ group, with posts pro and anti, is like hearing the bigoted chants of two opposed gangs burning with hatred for each other.

There has been an unexpected moment of redemption, though. In the run-up to 20 May, atheist and humanist students in the University of Wisconsin-Madison chalked stick figures on the ground of their campus, captioning them ‘Muhammad’. The Muslim Student Association found a witty way of responding, not by erasing the images, but by adding boxing gloves to the figures and the word ‘Ali’ after ‘Muhammad’.

Maybe if South Park had gone for the same visual gag, the whole thing might never have happened.

Comment (1) |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|