|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Category: travel

|

|

|

|

Heaven open on Holy Patmos

Posted on 02 May 2013, 3:49

Seven churches: Intro Pergamum Thyatira Smyrna Laodicea Philadelphia Sardis Ephesus Patmos

My sets of pics for this post: Patmos

Leaning against the ferry rail, the black water of the Aegean slid past below me, lit by the full moon high above. I saw dimly a small island shaped like a flat pyramid, darkly mysterious, as we sailed past. I leaned out and far ahead in the night were tiny lights – the lights of houses on the island of Patmos. It was 37 minutes past midnight and the words of John’s Apocalypse came into my head…

After this I looked, and, behold, a door was opened in heaven: and the first voice which I heard was as it were of a trumpet talking with me; which said, Come up hither, and I will show thee things which must be hereafter. And immediately I was in the spirit…

John, the author of the letters to the seven churches, was exiled here for his faith in the 1st century, and now, 2,000 years later, my father and I were arriving to complete our journey to this place where heaven was opened.

After our boat docked, we walked through sleeping streets pulling our cases on wheels. The hotel reception was closed, but five keys were on the counter with names sellotaped to them… none of them ours. So we took two at random and bedded down for the night.

I woke after an hour or two from a dream in which hundreds of people were walking up the street to our hotel, dragging their cases, the hundreds of rolling wheels filling the island with a great roaring noise, and all the people inexorably marching to claim the room they had booked and I had stolen.

Awake in the dark, it felt like a updated scene from the Revelation, with the Beast and the Whore of Babylon checking in their luggage. This island has something spookily spiritual about it.

Next morning, we walked down to the port town, Skala, which curls around a bay lapped by deep, transparent blue water. The sun was shining madly.

The town is all restaurants patrolled by cats, craft shops stocked with sponges and shells, narrow streets revealing whitewashed, domed churches, Greek men hurtling by on motorbikes, Orthodox priests flapping or pausing to pinch the cheek of a child, shop windows full of icons, fruit sellers at the harbour, men busy doing nothing at a taxi rank.

Over coffee at a streetside café we got talking to the owner and complimented him on the island. ‘It’s a beautiful place,’ I told him.

‘Yes,’ he agreed. And then with hardly a hint of smile: ‘But it is also a holy place.’

High over the town on a hill is the Monastery of St John the Theologian. Late morning a taxi bore us up a winding road through pine trees, past a stonemason’s yard with signs outside advertising petra and marmara (stone and marble), until we reached the Cave of the Apocalypse, below the monastery.

This is where the exiled St John received his Apocalypse, according to local tradition. And it is where our seven churches pilgrimage was completed.

It is 40 steep steps down to the cave and my father is 85, but he’s also intrepid and we made it down arm in arm almost without a pause. Over the doorway before you enter the cave is a bright icon of St John in red robes holding a pen in one hand while a pen holder is under his other arm. The book he holds is open at a page full of Greek text which reads: ‘In the beginning was the word…’

We stepped through the doorway and into the place where that word was alarmingly revealed. Although an Orthodox chapel has been added to the front of the cave, the powerful forms of the bare rock on your right are what immediately command your attention. The entrance to the cave is low, while the roof rises behind it, reminding me of a huge fireplace, which seems right. Holy fire touched down here.

In a deep recess is a place of prayer, marked by red velvet draped over the rock and hanging silver oil lamps above. The cave reminds me of the prophet Elijah in the Old Testament, who stood in the mouth of another cave and experienced earthquake, wind and fire, but found God instead in a still small voice. St John’s writhing visions seem to be the reverse of Elijah. They have nothing of the still small voice, but all of the earthquake, wind and fire.

And yet the atmosphere in the cave was quiet and expectant. We were there entirely on our own, which I think must be quite unusual.

A small window shows the view from the mouth of the cave. Below are the trees, fields, hills and bays of Patmos, and then the sea, and then the eastern sky. As he sat here, St John looked out towards the faraway seven churches of Asia Minor.

I sat with my father on a wooden bench and we prayed together. The cave has a beautiful acoustic. It is a place where the door of heaven opened for St John like the door of a furnace. In a small way, it opened for us too, but breathed only peace at the end of a journey.

Comment (0) |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

A wonder on every corner of Ephesus

Posted on 27 April 2013, 2:41

Seven churches: Intro Pergamum Thyatira Smyrna Laodicea Philadelphia Sardis Ephesus Patmos

My sets of pics for this post: Basilica of St John, Ephesus city

After a lifetime of familiarity with the Bible, it’s a strange thing to see biblical names on a modern road sign. But that’s what I’m seeing now as I look out the car window: a blue sign above a roundabout tells us that Efes (Ephesus) is 3km to the right, just a chariot dash.

Ephesus was one of the great cities of the ancient world, famous in its time, but more than that, it’s one the ‘ians’ and therefore famous ever since and for ever. Galatians, Philippians, Colossians, Corinthians, Ephesians… these ‘ians’ of 1,000 indifferently read lessons in church have made me very curious about visiting this city.

There are two letters to the Ephesians, of course: the long one which comes after Galatians, and the shorter one by John in his Apocalypse.

We started at the (ruined, naturally) 6th century basilica of St John in nearby Selçuk, which is an inspired choice as from the west end of the church you get an angel’s eye view of the geography of this place: the surrounding hills, the broad, fertile valley between them which ends in the distant sea, the small hill on the left behind which Ephesus is hidden.

By tradition, the church is the final resting place of St John and a white marble slab laid on the floor of the chancel, guarded by four columns, is the modern memorial of that.

In the church is an ancient stone baptistery which any Baptist church would be proud to have. It’s set in the floor with steps leading down one side into a small, circular pool, and then steps up the other side. Next to it is a square slot cut into the marble floor which archaeologists think was once filled with oil for anointing the baptized Christians.

Since it’s such an old baptistery I wonder if they followed the tradition of the early church by giving the newly-baptized milk and honey as they ascended from the pool: a sign of passing through the waters of Jordan and entering the promised land.

By the time we reached Ephesus itself, the day was hot and the tourists were out in large numbers. We worked our way down from the top of the site. Once you’re through the turnstiles, you’re basically following the main street down through the old town, with education, entertainment and distraction along the way.

Within a couple of hundred metres in a variety of temples, statues and carvings we met Hermes with his winged shoes, Tyche the goddess of luck, Hercules out walking a lion and the hissing hairstyle of Medusa. We saw the numerous cats of Ephesus lounging on mosaic floors or draped over column capitals. We paused at the famous bogs of Ephesus, where wealthy men sat on a marble shelf punctuated by holes and a channel of running water at their feet served in place of loo roll.

We spent a while at the Library of Celsus, which surely boasts one of the most handsome facades of all classical architecture. Looking at the way the lintels on the columns swap places between the first and second storeys, I wondered if it had inspired MC Escher in his drawings of impossible buildings.

The library opened for reading in AD 100-ish and issued its last book just 170 years later when it was demolished by an earthquake. Its columns were raised again in the 1970s. Four statues stand beside the doors welcoming readers, and I loved seeing Sophia and Episteme (Wisdom and Knowledge) among them. The whole building reads like a homage to the beauty and improvement of reading.

It’s easy to get classical overload here: the baths, the market, the fountains, the theatre, the advert for the bordello just up the street carved into the pavement. The house where Anthony and Cleopatra used to meet up. After a while your imagination collapses with the effort of trying to take in the idea that these things happened here, and that if you’d been here at the right time you’d have seen them happen before your eyes.

Visiting Ephesus wasn’t a spiritual experience for me. Instead it was merely amazing, with a new wonder around every street corner.

I think this place is powerful in opening you up to the classical and pagan context for early Christianity. It helps you understand why the faith of the early Christians was the shape it was. Somehow, seeing the hills John, Paul and the other first believers saw, and walking in their streets under the heat of the Asia Minor sun, gets you under the skin of the letters to the seven churches and the episodes in the book of Acts.

Even though I don’t know it for sure yet, I think visiting these churches will add a lot of width (and maybe even depth) when I read the texts of the New Testament.

Comment (5) |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Demons and crosses in Sardis

Posted on 26 April 2013, 3:31

Seven churches: Intro Pergamum Thyatira Smyrna Laodicea Philadelphia Sardis Ephesus Patmos

My set of pics for this post: Sardis

Sardis, where John’s fifth letter to the churches was sent, is now Sart, a little village lost in the folds of lumpy hills at the foot of Mt Tmolus, which in contrast is a brutal slab of stone. I just had to stop the car and stand on the side of the road to get a picture of the village and its mountain as they look so good together.

I also asked a couple of local women to let me take their picture as they were (I think) knitting, with their feet up on chairs. Their brightly coloured clothes and headscarves are worn by women throughout this region of Turkey.

Back in the day, Sardis had one of the biggest synagogues in the western world, and we called in there today. Its vast size and luxurious mosaics tell us that there must have been a very big Jewish population living here in the 4th century AD. That was a bit of a surprise when archaeologists unearthed the synagogue in the 1960s, as it had been assumed Judaism was declining at the time, with Christianity taking off.

My father just loved being here in this synagogue and could easily identify the different parts of the building, including the marble sanctuary where the scrolls of the Torah were kept. He used to be a church organist, but when he was a student, he answered a newspaper ad from a synagogue which was looking for an organist, as he needed the extra cash. They appointed him, and he’s been there ever since, now over 60 years.

The place here which seized my imagination was the ruined Temple of Artemis, which is in a remote field outside town, overlooked by curious hills shaped like pointed hoods. The place is lonely, melancholy and haunted – and maybe a bit dark too.

The old temple and its columns are colossal and when you climb up onto the platform with its floor and steps infilled with grass, or walk among its avenues of broken, blackened columns, you get a real feeling for the occult potency of paganism. We were there in the late afternoon, with long shadows on the grass, which just adds to the feeling.

The worship of Artemis eventually came to an end, of course, after hundreds of years. Who was the last priest here, and what were his feelings as he left the temple, or lay dying, knowing that he was the last of his line?

When the temple was abandoned, the local Christians in the 4th century still feared the old building, thinking it was inhabited by demons. They apparently carved crosses into it to break their power. I went on a search of the east doorway to see if I could find them. At first I found only bees, which have built thriving nests at this end of the building, but then, in the massive stone doorposts I found small, roughly carved crosses.

I also found a little, brick-built Byzantine church tacked onto the southeast corner of the temple (pictured above), perhaps for the same reason, to negate the power of the old religion and celebrate the power and joy of the resurrection.

This church, like the temple before it, is also a ruin. It’s depressingly like finding the graveyards of two religions next to each other. The only religion in town is in the mosque. I can’t find a church, congregation or gathering of any kind (Orthodox, Catholic, Armenian or Protestant) in modern-day Sart when I look on the Net.

‘I know your deeds; you have a reputation of being alive, but you are dead. Wake up! Strengthen what remains and is about to die,’ says Jesus in the letter to the church in Sardis. But nothing remains now.

I found some interesting stuff on the Net about the state of Christianity in Turkey: Christians in Today’s Turkey (2012); The Armenian Weekly’s List of Churches in Turkey (2011); Jesus in Turkey by Christianity Today (2008).

Comment (1) |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Wreck of faith in Philadelphia

Posted on 25 April 2013, 1:28

Seven churches: Intro Pergamum Thyatira Smyrna Laodicea Philadelphia Sardis Ephesus Patmos

My set of pics for this post: Philadelphia

There’s not much left of Philadelphia, despite it having the most modern-sounding name of all the seven churches of the Apocalypse. All that remains is a piece of ground the size of a postage stamp, and on it the noble wreck of a gigantic church in a garden neatly tended with rose bushes and palm trees.

The church is dedicated to St John, in keeping with its spiritual link to the visionary exile of Patmos. Churches with the St John name keep cropping up on this tour, with branches of the franchise in Ephesus and Pergamum as well as here. The names of ancient churches say a lot, and these ones tell us that the St John connection was deeply felt and treasured.

We drove to Alaşehir (Philly’s modern name) this afternoon after lunch outside Laodicea in a roadside restaurant the size of a palace, with its own luxury swimming pool. We luckily arrived just before a couple of coachloads of Japanese tourists debouched into the restaurant and began raiding the vast buffet of delicious Turkish food. These restaurants are definitely the way to go if you’re ever travelling in Turkey.

Ninety minutes of driving later and we pulled up at the St John’s postage stamp. It’s set in a sleepy neighbourhood of houses, trees, birdsong, men sitting out on the pavement talking and one or two shops. The little blue mosque opposite the church gate has a minaret that looks like Thunderbird One.

Beyond the gate, three massive piers which once marked the great church’s crossing erupt from the ground and tower over the garden, while only the footprint of the fourth pier remains in a great hole five or six metres deep. The piers were originally lined with slim slabs of fine marble, but now their naked Byzantine brickwork provides a nesting place for birds.

In a little office at the back of the site, Umit, a tall, handsome gentleman, the guardian of the monument, sits at his desk enjoying a quiet smoke and a cup of mud-like Turkish coffee. He tells Seher, our guide, that before the separation of the Greek and Turkish populations in 1923, the Muslim and Christian families here lived happily together, and remarkably, that some Turkish people became Christians.

He directs us to gravestones in the gardens which witness to this. They were brought here from the local churches when the Greek families left and the churches were turned into mosques. One of them from 1890 has the surname Lokman in Greek lettering. ‘It’s a very Turkish name,’ Seher tells me.

The sad exodus of the Greek population from their ancestral homes in Turkey to modern-day Greece marked the final full stop of the Christian mission to Asia Minor led by St Paul and St John in the 1st century.

‘These are the words of the one who opens and nobody shuts, who shuts and nobody opens,’ says Jesus in the letter to the Philadelphian church.

What does it mean when the most dynamic region of growth in the early church – this region of the seven churches – is shut with no possibility of opening 20 centuries later? What does it mean when the living faith of the Philadelphians ends up as a giant brick wreck in a garden?

I suddenly realise something obvious: every one of John’s seven churches is now dead. But it feels most obvious here in Philadelphia. Thankfully, we leave before the call to prayer can bang in the final nail.

Comment (0) |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Hydraulic cranes of Laodicea

Posted on 24 April 2013, 2:54

Seven churches: Intro Pergamum Thyatira Smyrna Laodicea Philadelphia Sardis Ephesus Patmos

My set of pics for this post: Laodicea

Laodicea is a bad place to build a town. You wouldn’t think so as you drive up the low ridge it sits on, overlooking the flat and fertile valley floor with distant snow-capped mountains floating magically above the nearer hills.

Today, as we pass between the stone towers of the eastern gate, we’re surrounded by dense banks of spring flowers, the poppies the deepest red you could think of, and birdsong sweet and intense.

It must once have seemed a good idea to build here. The town is slap on the major east-west commercial road across Asia Minor and made itself rich in trade and banking just by putting itself in the right place.

The Laodiceans must have loved everything about their beautiful and prosperous setting – except for the earthquakes. Quakes visited the city in the 1st century reigns of the Emperors Augustus, Claudius and Nero, and that final one in the year 60 was a raze. Nothing was left standing. The city was rich enough to rebuild itself without outside aid, but it toppled again around the year 500 and then again around 600, after which they called it a day. There have been no Laodiceans in the 1,400 years since.

But one of the first things we see as we walk here today is a giant yellow hydraulic crane raising and positioning huge blocks of ancient stone. Sending one of those babies back in time would be an untold blessing to the ancient builders, I can’t help thinking. Turkey is putting vast sums of money into excavating and reconstructing the ruins, with hundreds of workers onsite. Laodicea is rising one more time, until the next seismic twitch.

We walk up the main street, the sun beating down, the lizards flicking between stones. Either side of us is an avenue of free-standing columns, and behind them are the broken walls and doorways of the shops which once did a roaring trade here. The arrangement of columns and shops is very contemporary and I feel at home.

For some reason, my eyes are drawn to the marble threshold slabs in the doorways, worn to a polish by the feet of customers whose shopping days are long gone, with the deep ridge cut in the stone where the vanished shop door would have shut tight. In the back rooms grass grows where wine, olives, fabrics, furniture and fruit were once stored.

At the top end of town we turn left and the street ahead is choked with large chunks of marble. Broken columns, snapped lintels carved with flowers, smashed slabs inscribed in Greek and even one or two battered crosses lie where they fell on a day of doom centuries ago.

We’ve seen a lot of ancient rubble the past couple of days, but the sight of this ruined street is oddly moving. All the beauty, ingenuity, aspiration and dignity of the Laodiceans lies wrecked here, down to the last little chip of stone with a bird carved in it, ground to forgotten gravel by the earth-shaking machine of time. Looking at it, you know it is also about you, and how you and your all-important life and culture will look a couple of millennia from now.

Having said that, Laodicea remains impressive and beautiful, from its elegant and spacious forum to the two theatres carved into the hillsides and positioned just right so they get air-conditioning from the afternoon breezes. The town had water piped in from the hot springs of Hierapolis, 8km up the road – although it arrived lukewarm. We see the terracotta pipes running down many of the streets.

That plumbing detail is an abrupt reminder of John’s letter to the Laodicean church, and it’s the most memorable of all the seven letters. ‘I know your works,’ says Jesus in the letter. ‘You aren’t hot and you aren’t cold. I wish you were one or the other, but instead you’re lukewarm. That’s why I’m going to vomit you out of my mouth!’

The ballsy language of that passage has always appealed to me. When you look at the wreck of the human home that was once Laodicea, you know that hard to hear, colourful language is sometimes the only thing that will do.

But actually, standing today in one of the empty streets, facing a doorway that was once someone’s welcoming home, but behind which is now a waist-high bank of earth carpeted in poppies, it’s the last section of John’s letter I hear in my head. The words are also famous.

‘I stand at your door and knock. If you hear my voice and open the door, I will come in and eat with you, and you with me.’

As long as we have doors to call our own, as long as we have ears to hear a voice, as long as we have love to open our hearts, God can come to us.

But only that long.

Comment (2) |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Smyrna on a dead speakerphone

Posted on 23 April 2013, 2:42

Seven churches: Intro Pergamum Thyatira Smyrna Laodicea Philadelphia Sardis Ephesus Patmos

My set of pics for this post: Smyrna

We knocked off two of the seven churches of the Apocalypse yesterday – Pergamum and Thyatira – but we’ve been staying in Izmir, which is ancient Smyrna, another of the churches. The trouble with Smyrna is that it was never abandoned to become a ruin, but instead became a busy port and the third most populous city of modern Turkey. So there’s not a lot of the Roman town left on the ground.

Our guide, Seher, had given this some thought, though, and took us this morning to a living church, St Polycarp’s on Necatibey Boulevard, just a few blocks from our hotel. It’s a Catholic church, one of the oldest in Izmir, and has a splendidly ornate interior. However, ‘I don’t think we’ll be able to go inside,’ Seher told us, ‘as you need to make an appointment many days in advance.’

This sounded a bit odd for a church, and when we arrived there was a speakerphone on the metal gate which picked up and then went dead when we buzzed.

On the immaculately painted church wall I spotted some large graffiti in red paint and wondered whether that could be a clue about why the church is security conscious. A church member came up to us on the pavement and gave us some embroidered crosses which he and his wife had made – and this sweet gesture more than made up for the unresponsive speakerphone.

The church is named for St Polycarp, who was a disciple of the apostle John back in the 1st century and was martyred here in Smyrna around the year 155. I’ve always loved his heartfelt and spirited answer when he was challenged by the local Roman proconsul to swear by Caesar: ‘Eighty-six years I have served him and he has done me no wrong. How can I blaspheme my king and my saviour?’

The proconsul’s response was to have Polycarp burned alive.

In the letter to Smyrna in the Apocalypse, Jesus says, ‘Don’t be afraid of what you are about to suffer… Be faithful, even to the point of death, and I will give you life as your victor’s crown.’ It’s clear that St Polycarp lived those words. They could have been written for him.

Like everything in John’s Apocalypse, Jesus’s words are sharp and challenging, whether you’re a Christian living comfortably in the West, or the church of a minority faith on Necatibey Boulevard with a speakerphone that goes dead.

Comment (4) |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Call to prayer in Thyatira

Posted on 22 April 2013, 4:43

Seven churches: Intro Pergamum Thyatira Smyrna Laodicea Philadelphia Sardis Ephesus Patmos

My set of pics for this post: Thyatira

This afternoon, our driver Pala drove us for an hour from Pergamum through dramatic mountains to the town of Akhisar, which was once Thyatira, a town famous for indigo, purple and the dyeing industry in general. It was bathos to be here after the feast that was Pergamum, though: just the ruin of a church founded in the 2nd century that is bang in the middle of a busy shopping area.

While I was looking at the fallen masonry, the call to prayer from a local mosque started up, and within seconds, two other mosques joined in. I find the call to pray beautiful and beguiling in its way, but it was a sharp reminder here of how Christian faith can die and fall into dust; how it can become the fulfilment of the letter to Thyatira in the Apocalypse.

Comment (0) |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Walking in Pergamum

Posted on 22 April 2013, 2:29

Seven churches: Intro Pergamum Thyatira Smyrna Laodicea Philadelphia Sardis Ephesus Patmos

My set of pics for this post: Pergamum

We were on the road out of Izmir by 9 o’clock, and Pala, the driver of our white people carrier who looks a lot like MP George Galloway and drives with the same sort of take-no-hostages philosophy, soon had us speeding away from the city. Our guide Seher started briefing us about the day ahead and showed us an excellent book we should have read before coming here, Mark Wilson’s Biblical Turkey.

Izmir is ancient Smyrna, the first of Revelation’s seven churches, but it’s now a city of 3 million people with houses densely carpeting the little hills, and precious little is left of the old Roman town. We stayed here last night, lulled to sleep by the neighbourhood mosque’s call to prayer and then rudely woken by it before breakfast.

Just over an hour later we stepped out in a wash of spring sunshine at the Pergamum cable car. Pergamum is perched on a rocky hill 300m above the valley floor and was once the ruling city of the region. It’s now a toppled ruin, with the modern city of Bergama sprawled across the valley below.

Exiting the cable car at the top, we were greeted by a small bazaar of colourful shops selling fruit, hats, postcards, t-shirts and little statues of the goddess Diana of the Ephesians. Handy if you want to take one home to worship.

Ignoring all that, we were soon on the ancient city’s acropolis, poking around the beautiful and melancholy fallen masonry of the Greek world. In the 1970s, some of the marble columns and lintels of the Temple of Trajan were raised from the grass where they had fallen centuries earlier, and they now crown the hill. There’s something timeless and dreamlike, seeing these gleaming white pillars against the deep blue sky.

The letter to the church in Pergamum in John’s Apocalypse says, ‘I know where you live – where Satan has his throne.’ John is highly hostile and exclusive in his faith claims, and all the temples, altars and shrines we saw today here – to Athena, Zeus, Demeter, Dionysus and the Emperor Trajan – must have riled John to bits and help explain his ‘Satan’ remark.

My imagination was snagged, though, by the Library of Pergamum, or what is left of it. The library was second only to the Library of Alexandria in the Greek world, and held 200,000 works in scroll and book form. In fact, Alexandria was so infuriated by its rival that it banned the export of papyrus in the hope that Pergamum’s supply of books would dry up. Pergamum responded by inventing parchment (the word derives from ‘Pergamum’) made of calfskin.

None of the works held by this amazing library remain here, though. All I could see was an avenue of broken columns where scholars once walked, and a wide pavement where the reading room once stood, with the wrecked base of a statue of Athena, the goddess of wisdom. Athena is now in Berlin – she was carried off there by zealous German archaeologists in the 19th century – while the 200,000 books were all handed over to Alexandria in the end, when Mark Anthony gave them to Cleopatra as a wedding present. The librarians of Pergamum must have died of grief as their books were carted off for ever.

We walked down to the dramatic hillside theatre, the steepest of the ancient theatres, where 10,000 spectators once watched Greek dramas; down to the vast gyms, which were on three levels, for boys, young men and adults; and on through acres of ordinary housing which now lie under mounds of grass.

We found a decent-sized tortoise stuck in the upended stones of one house and rescued it. In a hall next to the temple of Demeter we saw fine floor mosaics with theatres masks – grinning and grotesque – depicted in medallions.

The vastness of the site gave me an appreciation of the splendour and power of Pergamum, and what the young church here was up against. To be a Christian in the early years of the faith, dissenting in such a potent cultural context, would require a lot of courage. Reading John’s letter again with the temples, roads, altars, gymnasia and theatre in mind, I can see him giving his readers some help by putting fire into their faith.

Comment (2) |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Off to the Apocalypse

Posted on 20 April 2013, 3:41

Seven churches: Intro Pergamum Thyatira Smyrna Laodicea Philadelphia Sardis Ephesus Patmos

Early tomorrow morning, my father and I fly to Izmir in western Turkey for a week rediscovering the seven churches of the Apocalypse. We travelled together last year to Germany, visiting the towns where JS Bach lived in the 18th century, but this time we’re going back to the world of 1st century Asia Minor, to the roots of his faith and mine.

Aside from having our hearts strangely warmed, the temperatures are going to be in the mid-20s (or mid-70s in the old currency) and it’s going to be good sitting outside for seafood and wine after so many months of winter.

The Apocalypse, better known as the book of Revelation, was written on the Greek island of Patmos. It opens with a series of mini letters – almost postcard in length – written to seven churches on the mainland of what is now Turkey. The letters are colourful and strongly worded, with a mixture of praise and promise, criticism and warning for each church.

We’re going to be visiting each of the seven towns (most of which are in ruins) and then sailing to Patmos for the final couple of days. John the Divine, the author of the book, was exiled here for his faith in the 1st century, and a highlight will be visiting the Patmos cave where it’s believed he received his visions and prophecies.

The Apocalypse was a book which almost didn’t make it into the New Testament because of its bizarre and nightmarish content. It has choirs of saints and angels, beasts with multiple heads and on each head a crown, a pitched battle between the forces of light and darkness, a smouldering lake of fire for the wicked and paradise regained for the righteous.

The Eastern Orthodox still won’t allow the book to be read aloud in church for fear of its horrors and mysteries upsetting the faithful. This is probably wise.

I visited the Victoria and Albert Museum in January and spent time looking at a vast 14th century triptych they have from Hamburg. It’s covered with scenes taken from the Apocalypse, and I snapped one of them, seen above. It gives an idea of the dense and fevered atmosphere of the book.

Will Self, in his combative introduction to a pocket edition of Revelation in the King James Version, says he found it ‘a sick text… a guignol of tedium, a portentous horror film.’

Aside from all that, I’m looking forward to immersing my head into the world which gave birth to the Jesus movement in the 1st century. Towns such as Ephesus are really familiar to me from reading the book of Acts, and the idea of actually walking those ancient streets is intoxicating. I’m hoping to blog about the experience day by day, so long as the bandwidth of Asia Minor holds up.

Comment (1) |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

90 minutes with Moltmann

Posted on 14 March 2012, 6:21

Jürgen Moltmann has a very infectious way of laughing. He fixes you with his bright eyes, a smile spreads across his face as he’s talking, and then comes the almost soundless laughter that sweeps you with it. I really hadn’t expected that from one of the 20th century’s most brilliant German theologians, and even less so from someone who powerfully made the case, after Auschwitz, that God is a God who suffers.

I visited him at his home in Tübingen last week, after a 10 hour train journey. The magazine which sent me to interview him, Third Way, didn’t want me to fly by plane, for the greenest of reasons, but it was a long journey to make for a 90 minute meeting. It turned out to be beyond rewarding, though.

The French and then German countryside unfolding outside my train window was beautiful in the early spring sunshine, but I had my head stuck in a book most of the way. Like an undergraduate with a late essay to submit, I was deeply into Moltmann’s brick-sized autobiography, A Broad Place (408 pages), which turned out to be an inspiring read. By the time I sank into my hotel bed at 2am, I was ready with my list of questions.

Professor Moltmann retired in 1994, but since then, six new books of his have been published in English, with a seventh currently in the works. He’s now 85, but several years ago when he turned 60, he said that he unexpectedly ‘became young and lively again’. His youthfulness in old age seems to have stuck. The first sign I saw of it came after I climbed the road up and out of old Tübingen, along the valley above the River Neckar, and found that the car parked outside his house had personalised number plates. I spotted the ‘JM’ straight away.

Inside, after he’d made me a dish of very weak tea (I estimate Pantone 726), he took me into his study, which is a broad, beautiful, light-filled room looking down the steep slope of his long garden into the valley. I always enjoy seeing where people work, and this room, where so much influential thinking took shape, was everything you could wish for.

With no computer in sight, I asked him if he used an Apple Mac. ‘I am an old European,’ he replied, amused at himself. ‘I use telephone and fax.’ He writes his books by hand and corrects a typewritten copy. ‘I like the combination of mind and hand,’ he said, and then added, ‘At my age, I am writing more letters of grief and consolation, and I cannot type a letter of compassion.’

I’d asked to see his study because I wanted to know what pictures he had in there, as some of his thinking has been shaped by meditating on images such as Andrei Rublev’s icon of the Holy Trinity. He showed me a Greek icon of the resurrection on the wall, as well as a postcard image of Marc Chagall’s Yellow Crucifixion, which he had tucked inside a first edition of his book The Crucified God.

‘For a long time this picture was my companion,’ Moltmann wrote in his autobiography, ‘and was a symbol inviting me to theological thinking.’ I don’t know of many Western theologians who have done this.

At the end of our 90 minutes, I had to dash to catch my train home, but as I was packing up I couldn’t resist asking him what his favourite hymn was. It’s a bit of a cheesy Songs of Praise question, but I was interested in what a theologian would do with it. When he hesitated to answer, I expanded the question by asking what are his sources of inspiration and consolation.

‘Mostly watching nature – and especially the sea. From Hamburg, we always spent our holidays at the seaside. I was always fascinated and had mystical experiences! The music of the sea is like the tone of eternity. Because this was here before human beings came and this will be there when human beings have maybe vanished from the earth.’

I shot a video of the interview and will be putting some clips from it online soon. I’ll post here when they’re up.

Comment (1) |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

The goal of pilgrimage

Posted on 05 February 2012, 7:33

Bach pilgrimage: Day 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | Photos

Saturday 4th February: This morning, my father and I took a walk. Out of the hotel, along the slippery-with-snow street, down into the subway and then out onto Reichsstrasse in the old heart of Leipzig, going south. On either side of us were dire buildings from the GDR era, one of them covered in blue and yellow panels and looking like the sort of block which would disgrace a South London estate.

We cut through past the old town hall, an overcooked piece of gingerbread which is 50 per cent larger than it should be, and then along Thomasgasse. Suddenly the goal of our pilgrimage slowly revealed itself around the corner of a building. We stopped to admire the Thomaskirche, standing pale and beautiful across the wide square in the freezing February sunshine.

I don’t think I could have felt one tiniest bit less happy than a pilgrim who has dragged himself bleeding along the Camino in northern Spain for a couple of months and who finally spies Santiago de Compostella on his horizon. We just stood there for a while and I felt that kind of bursting happiness.

Not many buildings do this to me. Hagia Sophia in Constantinople certainly did, 15 months ago, but I wasn’t expecting to experience something of that feeling again with Johann Sebastian’s church in Leipzig, where he was cantor for 27 years until he died in 1750.

We walked around the west end of the church and stopped at the huge statue of Bach on the south side. I remember the statue from black and white record covers in my Dad’s classical music collection in the 1950s, and I just had to snap a picture of him with it. I owe him so much for introducing me to Bach through those albums and through his own music-making, and taking the picture completes a 50 year-old circle.

Then up the steps and into the church. We could hear organ music as we approached the door, and as it opened, the joyous music of Nun danket alle Gott came out to meet us and pulled us in. A small congregation was singing the hymn in the choir and its English words immediately came to mind…

Now thank we all our God,

With hearts and hands and voices,

Who wondrous things hath done,

In whom this world rejoices;

Who from our mothers’ arms

Hath blessed us on our way

With countless gifts of love,

And still is ours today.

I’m not ashamed to say that the thought of my mother and the lifelong blessing she was to me immediately brought me to tears. Nearly a year after her death, I’m still in a winter of grief for her. And I wished, like Digory in CS Lewis’s The Magician’s Nephew, that she could be here, healthy and strong again, to be with me and my Dad, enjoying this amazing moment of arrival.

The church in its current incarnation is a whitewashed Lutheran hall. It has deep red tracery on the ceiling which falls into the pillars slightly randomly, as the pillars have somehow lost their capitals. The effect of that is a bit awkward and distracting. The choir is bent at a distinct angle to the nave for no reason I can imagine, but that feels loveably eccentric. The overall effect is of expansive, light-filled space, and when the organ ceases, the reverb is just right. The old building (just over 500 years) has an acoustic Bach must have enjoyed working with.

Standing with the other pilgrims on the edge of the choir, which was roped off, the large slab covering the grave of Johann Sebastian Bach was just a few feet away, alone in the centre of the paving, with flowers all around the edges. Bach’s unmarked grave was rediscovered in 1898 and his remains were moved here in 1950, 200 years after his death.

We had planned to cover various places in Leipzig today, but we basically spent the whole day in and around the Thomaskirche: in the shops, for example, where the Bach tat included chocolate coins, German wine and a USB memory stick, all printed with the bewigged head of JSB; and in the museum opposite the church, poring over the original, autograph parts for a Cantata played here in 1723.

Sitting in a cafe across the street at 2.15pm, drinking delicious, hot vegetable soup and waiting for the start of a motet in the church at 3 o’clock, I noticed large numbers of people arriving at the church door and kicking the snow off their feet, 45 minutes ahead of time.

The church stages motets every Friday and Saturday, and when we’d finished our soup and sat inside, the church was pleasantly full. I had thought we’d probably be there with a few diehards, since February is hardly the height of the tourist season.

The programme began with Bach’s Prelude and Fugue in C major (BWV 545). Its long pedal notes, sustained while the higher notes spiral around them, took me back to when I was a kid and I’d go forward at the end of a service while my Dad was playing the post-service music, and I’d watch him in a kind of awe.

He’d be sitting back a little on the organ bench, absolutely focused on the sheet music, his feet walking and then running on the pedals, his fingers glancing off the keys, his breathing sharp with the effort of it all, and the music lifting, rising, flying, soaring. It was the physical energy on the bench and the spiritual effect in the heart. And it was utterly magical, with my father as the magician.

In the Thomaskirche, I couldn’t help inclining towards him and noticing how he responded in this fulfilling moment of hearing Bach’s music, which he had made his own music, being played in Bach’s church.

Does it make any difference listening to the music of JS Bach in the church where he is buried? Do you understand his music any better if you walk his path to work? Is it odd to find it consoling that his bones must vibrate when the colossal, 32ft Großer Untersatz pipe sounds in the Thomaskirche? Why go on pilgrimage in search of Bach when you already have the music anyway?

I can only say, sitting in this church and hearing this music that is in my own bones, that I’m glad my father asked me to make this journey with him, first when I was a child, and then today.

Comment (4) |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

The invisible composer

Posted on 04 February 2012, 7:49

Bach pilgrimage: Day 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | Photos

Friday 3rd February: My Dad and I arrived in Weimar last night and this morning took a 20 minute walk into town to discover the meagre show the town puts on for Johann Sebastian Bach. He was here twice: for a few months when he was 18, and then again in his early 20s when he was organist and concert master at the overblown court of Duke Johann Ernst for nine years.

His stay here ended when he spent a month in the clink for telling the Duke that he wanted to leave and take a job elsewhere. Despite that local difficulty, these were happy years for Bach. He was newly married to his first wife, Maria Barbara, and their first kids were born and baptised here in the Peter and Paul Church. He was rapidly growing as a composer and absorbing influences from Italy and elsewhere.

You’d think that any city, given nine formative years in the life of the world’s best known composer, would respond by doing everything it could to celebrate such fabulous good luck. But not Weimar. It’s much too concerned with its contribution to in-house German culture in the form of Goethe, Schiller and Herder, to pay much attention to JSB.

The only public mention of Bach we could find today in the centre of town was a plaque on the wall where Bach’s house used to be. Why Weimar has rudely turned its back on Bach is hard to fathom. Maybe it’s never forgiven him for wanting to leave.

The city is beautiful though and proud of its appearance in a way that would put pretty much any British town you could mention to shame. Dad and I took a walk in the bright sunshine from young Bach’s disappeared house, across the Markt square, accompanied by the prettily ringing bells of the town hall, to the Schloss, the local Duke’s palace, where Johann Sebastian worked. His commute must have taken him five minutes, tops.

Every day he passed through the palace’s old gateway and beneath the tower, which survived when the palace Bach knew burned down in 1774. I can recommend following his walk to work as an act of pilgrimage. Anything which helps reclaim his place in this rather inward-looking town is good.

The Schloss has an extensive collection of paintings by Lucas Cranach the Elder, including several of the most famous pics of Martin Luther, but I especially enjoyed their collection of medieval altarpieces, crucifixes and devotional statues which somehow survived the Lutheran bonfires to end up here. I took pictures of several of them until a rather severe attendant shook her head at me. I’ve put a selection of my shots into a Flickr set called Devotional statues... they’re beautiful and moving, and clearly made by people who knew what death and suffering looked like.

Rivalling that for best moment of the day was a late lunch in the cellar bar of the famous Hotel Elephant. The hotel has been here for 450 years and is right next to Bach’s now vanished house, so he must have supped here whenever Maria Barbara wanted a break from the cooking.

As we ate our wild pork (with red cabbage, poached pear and walnut croquettes, served on nicely hot plates and easily the best food I’ve eaten out in ages) in the Elephanenkeller, our enthusiastic waiter brought us some info sheets about the hotel, which has a long and mostly distinguished history, including visits from Liszt, Tolstoy, Goethe, Hans-Christian Andersen and… er… Hitler, who used to address crowds in the square from his own little ‘Fuhrer balcony’ over the front door.

I was fascinated to read that in 1998, some newly opened rooms in the hotel enabled the ‘demythologisation of Suite 100, the rooms used by Hitler during his visits’. I had never realised before today that hotel rooms could be demythologised. But 10 out of 10 for them for being honest about their dark past, when swastikas hung from the hotel windows, and attempting to expunge it.

Thoughts of that past lingered as we left Weimar this evening. We passed two buses on our way to the autobahn. The first displayed the destination Planetarium. The second, Buchenwald. The concentration camp – the first opened by the Nazis – has been preserved and is just six miles north of the city.

Comment (1) |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Bach’s angel in the roof

Posted on 03 February 2012, 7:05

Bach pilgrimage: Day 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | Photos

Thursday 2nd February: We had to leave Eisenach today, and the classy Steigenberger Hotel, which serves the best breakfast this side of the 18th century. But before we left town, we called in on the Georgenkirche and then the Lutherhaus.

Bach was baptised in the kirche and Luther was a student in the haus, but sadly the latter wasn’t worth visiting. Unless you enjoy laughing at dented mannequins taken from 1980s shop windows and recycled to look like people in Luther’s time, and the whole thing failing really, really badly. Which I do, of course. But it’s not for everyone.

The Georgenkirche was something else, though. It’s where baby Bach was baptised just two days after being born in March 1685. In the porch we found an imposing statue of Johann Sebastian looking very angry indeed and with his left foot thrust forward, as though he’s balancing on a skateboard. He doesn’t look much like Bach, which is maybe why he’s hidden away indoors. But I noticed that the left foot is bright brass, while the rest of the statue is black, so the pilgrims must touch or kiss it as a sign of respect. I gave it a kiss on my way out as a thank you to JSB.

The church is baroque, with a vertiginous three-decker gallery, and right at the front, in the centre, is the font where Bach first made contact with faith. I really loved the church, which felt old and well used by generations of Christians, and (on a more trivial note) was painted in cool neutrals, which seemed strangely contemporary. High up in the gallery at the back, squeezed up against the ceiling, is the church’s organ. A leaflet on the bookstall listed all the stops on this three manual monster, very few of which I recognised.

Back outside (the temperature by now a painful minus 11), we picked up our hire car, found the 88 road and settled into the drive to Ohrdruf, where 10 year-old Bach went to live with his older brother, an organist, after his parents died within nine months of each other.

We drove along the edge of the Thuringian forest, the trees outlined by snowfall on the branches, the long shadows of pines corrugating over the fallow fields powdered in white, wood smoke lazily rising straight upward from the few houses we passed. The little, rounded hills were just as I’ve always imagined Bach country and I could easily picture the bands of the family’s musicians walking from town to town. The whole landscape feels rich with memory and nostalgia.

There’s a dark side to that, though, as these landscapes breed isolated villages and deeply conservative ways, and it’s where nightmares straight out of the Brothers Grimm can be hidden and then dramatically emerge. Driving through, I could feel that, alongside the sunnier stuff.

At Ohrdruf, the lumpy landscape has been ironed flat by God, and the town itself is dull and uninterested in its most famous resident. The whole place was closed up tight at lunchtime, when we arrived. Cafes and restaurants had their doors firmly shut. My advice is to put your foot down when you reach Ohrdruf as it’s not worth the stop.

As we drove on towards Arnstadt, where Bach got his first organist job at the age of 18, the flat plain suddenly gave way to a descending valley, the road at first passing straight between long avenues of trees, and then winding through fields and woods, the winter sun splashing through the trees onto the frozen earth. It was just magical, and I can’t think it’s better in summer.

We ended the day in the market square of Arnstadt, looking around the church of St Boniface, the ‘Bach Church’. It’s another baroque splendour, with wedding cake tiers inside and an angelic-looking organ in white and gold fluttering in the roof. This is where some of Bach’s best toccatas and fugues were composed and first heard by people sitting in the pews below.

But thinking about it, the idea of a first ever performance of Bach is a bit unimaginable, actually. It might be because it’s always been around, but Bach’s music seems eternal: he didn’t compose it, but discover it. Michaelangelo described artistic creation using the language of discovery – ‘Every block of stone has a statue inside it and it is the task of the sculptor to discover it’ – and in Bach’s case it’s as if the music was somehow always out there and his brilliance was to hear it himself and then make it audible for everyone else.

But there was a first moment when those torrents of sound fell upon human ears. And it happened here. The old place feels touched by undeserved grace.

Comment (1) |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Ein feste Burg

Posted on 02 February 2012, 12:31

Bach pilgrimage: Day 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | Photos

Wednesday 1st February: Waking up this morning and looking out of the hotel window confirmed what I thought from last night: Thuringia really is rather lumpy. Small hills rise on the edge of town and the biggest of them, a crag, stands over Eisenach and is crowned by the Wartburg, the ‘mighty fortress’ of Luther’s bold hymn, Ein feste Burg. That was our destination this morning, and we took a taxi straight after breakfast, as I think it would be an hour’s walk to get up there on foot.

Once there, we bought tickets to a guided tour, if only to get out of the icy wind swirling round the castle’s courtyards, but the tour (which was in German, with an English booklet for language sluggards like me) was through a series of interesting but unheated rooms with our guide staying a bit too long in each of them.

Despite its ‘mighty fortress’ reputation, the Wartburg’s contribution to Germany has been cultural rather than military. For centuries, it’s been a place of architecture, poetry and song and inspired Richard Wagner’s opera Tannhäuser – not that I’d know, as I’m decidedly not a fan of Wagner – but my leaflet told me it was so.

I was amazed to read in it that according to the legend which inspired Wagner, a singing contest was staged here in the 13th century, in which six minstrels sang for the local ruler, Hermann I. Unlike The X Factor, the winner was not promised a recording contract and a guaranteed Christmas smash single, but the loser was promised immediate execution at the hands of the hangman. Surely Simon Cowell is familiar with this story? He must know that putting the losing contestants to death would build audience share. It’s the show’s natural next step.

Dermot O’Leary: What would it mean to you to win The X Factor?

Talentless contestant: Well, not being strangled on live TV would be nice.

But the reason my Dad and I came up here this morning was for Martin Luther. He was ‘kidnapped’ by masked agents of a friendly ruler, Frederick III, when his life was in peril in the winter of 1521-22 and hidden in the Wartburg. He spent those no doubt freezing months making the first translation of the New Testament into German, which was a hugely subversive act in those times.

Our last stop on the guided tour was the Luther room, his wood-lined pad during that winter. Even though it’s almost 500 years since he was here, seeing the round-topped door to his room ajar, I felt like knocking on it before entering. But the room is sadly empty of the fierce and impatient presence that once filled it.

Instead, the wood panelling is covered with carved graffiti from devout Lutherans who were here before me. IB was here in 1646, for example, while someone called Clueben left his mark in 1715. If this was in England, the room would be obsessively wired with CCTV to stop new carvings by fans, but thankfully that’s not happened here. Apparently, even the Stasi knew when to stop monitoring people.

Luther hated relics and risked his life to protest against them, but this room has that relic atmosphere to it. You feel in touch with Luther as you stand in it. Despite his many flaws and sins, you feel thankful for his stand against absolute religious power.

After a coffee, we went back down to Eisenach and landed in the Bachhaus, where it was once thought young Johann Sebastian was born and lived his childhood years. While that story has now been dropped, the house is a comprehensive Bach museum and performance place.

We arrived just in time for the house’s small collection of period keyboard instruments to be warmed up for a small, appreciative audience (of mostly Japanese students, plus me and Dad) in the instrument hall. I was pulled out of the audience to operate the bellows on a baroque chamber organ – pulling on two stout leather straps which gradually retracted into the organ case – while our guide-musician ran through some numbers from Anna Magdalena’s Notebook and other Bach pieces.

The house, which dates from Bach’s time, has been supplemented by a handsome building next door in the best German modernist style, with large, open, beautifully lit spaces. My Dad settled into one of the many perspex bubble chairs hanging from chains in the ceiling, and listened to Bach on a plumbed-in iPod. I walked round a brilliantly documented exhibition of how Bach has been pictured in paintings and engravings, and why it matters. Our three hours there simply vanished.

I hadn’t clocked before visiting the house how theological Bach was. He owned 81 fat volumes of theology at the time he died. But more than that, his huge copy of the Bible is filled with underlined words and notes jotted by him in the margin. The Bible is Luther’s, produced in the dead of winter in his lofty study in the Wartburg.

Bach’s Bible scribbles and the graffiti of Luther’s fans are an unlikely pairing, but they point to something out of this world happening in the unassuming town of Eisenach 500 and then 300 years ago.

Comment (0) |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

In Bach’s own country

Posted on 01 February 2012, 6:34

Bach pilgrimage: Day 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | Photos

Tuesday 31st January: I’m travelling today with my Dad to the little town of Eisenach in eastern Germany, which is the birthplace of Johann Sebastian Bach. We’re here for a week of pilgrimage, travelling to the towns and cities where Bach lived and worked. It’s a journey I’ve wanted to make with him for a long time, but family circs have prevented it from ever happening before today. So finally picking up our suitcases and heading off for the tube feels like a good moment to be alive.

There’s a lovely episode in Dylan Thomas’s play Under Milk Wood, which poetically captures life in a small (and small-minded) Welsh town. The church organist, who rejoices in the name of Organ Morgan, is having a conversation with his wife, who has been droning on a bit.

Mrs Organ Morgan: ... but they’re two nice boys, I will say that, Fred Spit and Arthur. Sometimes I like Fred best and sometimes I like Arthur. Who do you like best, Organ?

Organ Morgan: Oh, Bach without any doubt. Bach every time for me.

Mrs Organ Morgan: Organ Morgan, you haven’t been listening to a word I said. It’s organ organ all the time with you…

Organ Morgan: And then Palestrina.

My Dad is not quite Organ Morgan, but he is an excellent church organist with a passion for Bach that eclipses all other composers. He was king of the organ pipes at church when I was a young child, and I was in awe of the powerful and beguiling music he conjured from this Mt Sinai of musical instruments. I heard someone on Desert Island Discs a while ago saying that when they were little, they confused God with JS Bach, and I know the feeling.

For several years in my teens and twenties Dad gave organ recitals and accompanied the university choir my Mum sang in. And he remains the gentile organist at a synagogue in Cardiff, where he has been making music, kippah on head, for over 60 years.

Bach was frequently on the record turntable when I was growing up in the 1950s, and I often asked my parents when I was 4 or 5 years old to put on ‘Side Six’, the final side in their three-disc recording of The Christmas Oratorio, which maybe has Bach’s most joyful and danceable melodies. It was only in my 40s that I learned that the German lyrics to these closing arias and choruses sing of the triumph of Christ over death and the devil, a theme which has always been important to me.

Today’s journey, by rail from St Pancras in London to Eisenach via Brussels and Frankfurt, was simple in theory. Sleek German trains would speed us south from Brussels, wowing us with their cool efficiency. But instead, our ICE train, which travels at up to 300kph, was abruptly cancelled for no good reason and we were left at the mercy of plodding local trains (three of them) and a bus, which eventually disgorged us, mid evening, in Frankfurt Hauptbahnhof. We caught the last train of the night for Eisenach and arrived to biting wind and minus 10 of frost. We’re deep in former East Germany, and on tonight’s evidence, it still knows how to put the cold in Cold War.

My Dad, 83, despite a day of lugging a case and climbing in and out of carriages, looks happy and content to be here on the platform of Bach’s birthplace. He stands patiently for an iPhone snap (seen above). He’s in Bach’s own country at last.

Comment (2) |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Heaven and hell in a country church

Posted on 09 October 2010, 4:47

Flying to Byzantium: Entry 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | Photos

Istanbul, Sunday: Tali and I emerged from the depths of Hagia Sophia and went to sit in the open air café in the gardens outside for a calming cup of coffee and cigarette after all that religious intensity. I don’t normally smoke, but it was definitely time for some nicotine-assisted reflection.

Meanwhile, great dollops of beautiful warm sunshine were being generously served up on Istanbul, and after a quick visit to a cash machine, followed by a stroll among the underground pillars of the Byzantine cistern of Yerebatan, which is across the road from Hagia Sophia, we jumped into a yellow taxi.

‘Can you take us to the Chora Church?’ I asked our small, moustachioed driver. ‘Yes,’ he replied. And then sped off in the opposite direction to the church.

There followed some back seat angsting over whether we were being taken for a ride, until our driver explained that the police had closed the obvious routes because the town was choked with tourists. We drove around the Saray point and up the Golden Horn, with more than enough to look at on the way: towering, historic mosques, noisy, colourful markets, people enjoying lunch on the street, sticking their faces into chicken kebab wraps, ferries roaring out into the lively waters around the Galata Bridge.

Ten minutes later and we swept left along a broad road and were suddenly alongside the massive medieval walls of Constantinople, looking at them from the outside, just as the Ottoman attack troops had done before the city fell to them in 1453. And then left again, through a great breach in the walls, and we dropped down a narrow street to St Saviour’s, the Chora Church.

One of the meanings of chora is ‘country’, and as this whole area was rural even into the 20th century, the Chora Church is basically the ‘country church’. Which sounds very sleepy to English ears – and there is something country in feel about this place. It has a shady, walled garden at the back, and over the wall I could hear a children’s playground. But far from being just another country church, St Saviour in Chora is a jewel of Byzantine art: rebuilt in the 11th century and then decorated with the most stunning mosaics and wall paintings during a six-year makeover in the 14th century.

If that sounds a bit serious, then stepping inside makes you realise it’s entertaining, too, because the scenes covering the walls and ceilings of this lovely building are full of incidental detail: the water jars being topped up at the wedding feast of Cana; children playing on the edges of the crowd in the feeding of the 5,000; an angel carrying a giant scroll with the sun and moon rolled up in it at the last judgment. This is medieval television and the glass pixels in the mosaics are tiny enough to make it hi-def.

As you walk into the church, you pass beneath a monumental head and shoulders of a fierce-looking Christ. This is titled, ‘Jesus Christ, the chora (land) of the living’. So you enter under a theological pun which plays with the church’s name and the words of Psalm 27: ‘I am still confident of this: I will see the goodness of the Lord in the land of the living.’

But the face remains powerful. In her book, The Irrational Season, Madeleine L’Engle describes visiting the Chora Church and seeing this image of Christ. She says, ‘I knew that if this man had turned such a look on me and told me to take up my bed and walk, I would not have dared not to obey. And whatever he told me to do, I would have been able to do.’

Like Howard Carter at the opening of Tutankhamen’s tomb, we saw ‘wonderful things’ as we walked around, but I was here mainly for one wonderful thing: a fresco I had seen long ago in a book and which has lodged in my heart and head ever since. I saved it for last. It’s in the church’s burial chapel, painted inside the half dome at the east end, filling the whole of that curved space.

Standing dead centre beneath the icon, Tali and I looked up and became for the moment its intended viewers. Its title is Anastasis, ‘The Resurrection’, and in it the most alive Christ you’ve ever seen strides through hell, seizes Adam and Eve by the wrists – just as you’d grab the wrist of a difficult child – and pulls them bodily from their tombs. Beneath his feet are the trashed gates of hell, and below that is Satan, bound like a slave and surrounded by broken locks, chains, jailer’s keys and other small debris from the infernal workshops.

But it is Jesus who commands the scene, and your attention. I’ve never seen him painted this way. Byzantine icons are famously formal and still, with the look of people who have been told to hold a pose and not move. But this Jesus is caught in swift and decisive movement. He captures the vigorous words of the Orthodox Easter liturgy…

Christ is risen from the dead,

trampling down death by death,

and to those in the tombs he has given life.

This is so far from the seven-stone weakling Christ I saw pinned up in Sunday school in the 1960s, and so far from the bleeding victim Christ of Catholic statues which weep, that it took my breath away when I first saw it. Like reading Mark’s Gospel, it made me want to follow Jesus then… and now.

Did Jesus rise from the dead? I don’t know. What I do know is that I’d trade just a glimpse of this image for a hundred evangelical books which try to argue ‘the case for the resurrection’ like a whodunit. The Christ shown here powerfully makes me want to believe, and my unbelief can go hang.

Having said all that, I stood still under the image: absorbed, gazing, listening in the few minutes of my life I was there. Madeleine L’Engle says she trembled with joy as she stood on the same spot. For me it was wonder freed from emotion, which I hadn’t expected.

I don’t know if I’ll ever be here again. But I live in the glow of it. I hope for the life and transformation promised here. I hope to be in the land of the living Christ.

Comment (3) |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Into the Mega Ekklesia

Posted on 06 October 2010, 7:19

Flying to Byzantium: Entry 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | Photos

Istanbul, Sunday: Up at 7.30, along the gloomy corridor to the hotel lift, and then up, the lift managing no more than a crawl, to the 8th floor. The doors opened and the sun burst in, and we walked out into a rooftop breakfast room floating above the city, with the whole sweep of the Sea of Marmara at our feet.

Tali and I sat dazzled by the light and hardly able to drag our eyes away from the view. The Marmara really is a handsome body of water, with the Prince’s Islands forming beautiful grey silhouettes in the eastern light, 10 miles distant across the silky water. The islands were so-named because unwanted minor royals were often dumped there in Byzantine times, with no access to Hello! or Grazia and the other essentials of celebrity.

Breakfast over, we took the tram to the Sultanahmet (the ‘Hippodrome’) district of town, which is the historic centre of old Stamboul. There we went straight to Hagia Sophia and entered the gardens on the west side, which have been turned into an orchard of ancient stone columns, each dug up at various sites around the city.

I could hardly bear to go into the Mega Ekklesia (the ‘Great Church’ as it was known almost from the time it was built in the 6th century), as I’ve imagined the moment for so long, so we loitered around the gardens first, admiring beautiful pieces of long destroyed buildings, some of them in such good nick they might just have come out of the sculptor’s yard.

But then we turned to the imposing doors and passed through the outer and inner porches and on into the church. The interior is such a delirium of space I had to lean against the doorway for the first few minutes to drink in what I was seeing.

Below, a polished marble floor of vast expanse; above, the dome ringed by its 40 windows, sailing weightlessly into heaven as it has done for 14 centuries; around me, a hundred arms raised… not in worship, but holding digital cameras. In the centre of the church, huge chandeliers hanging from the heights above to hover within touching distance of the people below, creating intimate pools of space.

Unlike all the domed cathedrals I’ve visited, here the dome is immediately visible from the church door, and so the visual impact of Hagia Sophia arrives at once, in a single, overwhelming instalment.

In the 10th century, a Russian prince sent ambassadors to Constantinople in search of a faith to replace his paganism. When they arrived in Hagia Sophia, they said, ‘We knew not if we were in heaven or on earth, for surely there is no such splendour or beauty anywhere upon earth.’

A thousand years on, and even though the church is now stripped of the Christian worship which once made it live, I can understand what they meant. Its vast spaces, its beauty and antiquity, even its faded grandeur and tangible sadness, all evoked in me the mystery and eternity which belong to God.

We walked up an ancient spiral ramp to the gallery, which gives stunning views down into the church. At this level you can see how the eight large medallions bearing Islamic calligraphy are constructed, each of them with a wooden framework. The medallions were only put in place in the 19th century by the Swiss architect tasked with restoring the building.

They complement the calligraphy right up at the highest point of the dome, which carries a famous verse from the Qur’an: ‘God is the light of the heavens and the earth’ (Surah 24:35). No Christian could argue with these words, but there is controversy over whether the calligraphy should be removed as it’s believed a much older mosaic of Christ lies beneath it. Christians of a more Puritan temper would probably side with Muslims on this one.

Beyond a marble screen in the gallery, I found the luminous icon of Christ which has been made famous on a thousand postcards, book covers and printed icons. The 14th century mosaic is next to a window and is thought to have been damaged by rain, so large areas of the jigsaw of tiny mosaic pieces are missing, but the heads of Jesus, plus Mary and John the Baptist, who stand on either side, are intact and beautiful. Each of them is shown against a glowing gold background in the world of eternity.

I was lost for a while in thought and maybe even prayer, standing before this noble and searching image of Christ. Just to stand before it is to be given dignity. And then I rejoined the crowd there, snapping like paparazzi before one of the surviving glories of lost Byzantium.

Comment (0) |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Welcome to a narrow paradise

Posted on 03 October 2010, 22:08

Flying to Byzantium: Entry 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | Photos

Acton to Istanbul, Saturday: Tali (my daughter) and I were late leaving the house to get to our local tube station, Acton Town, comfortably in time for the first tube of the day to Heathrow, so we had to do it the uncomfortable way instead: racing along the dark streets noisily dragging our cases-on-wheels behind us.

Even so, as we hastened I noticed the horned moon in the sky above us, a white, waning crescent. It struck me as a good sign for a trip to conquer Constantinople, as the moon was famously in this phase when the city fell to the Ottomans in 1453.

Five hours later we were hurtling in a taxi from the airport into Istanbul, rear seatbelts not working, Turkish music blaring, the meter ticking over gleefully. Suddenly out my window on the left I saw the brown and white stripes of the massive walls of Constantinople, where they come down to the Sea of Marmara, which was on our right. The walls finally failed in the Ottoman siege, which is why Istanbul is now a city of mosques rather than churches. I’ve always imagined entering the city from this side, through the walls, so this was an advance thrill of the city.

‘Welcome to paradise,’ was how the receptionist at our hotel in the old town greeted us, but paradise turned out to be a very narrow room: two beds with an 18 inch strip of carpet between them. So we were quickly back out on the street waving down a taxi for another hotel.

Our new taxi took us right around the end of the peninsula, giving us a lightning tour of the Bosphorus, packed with ships, and then the Golden Horn, with the coloured buildings of the Beyoglu district heaped up on the other side.

Our driver either hadn’t done ‘the knowledge’, or was deliberately taking us the most lucrative way around town, and we quickly hit the Istanbul rush hour. Which he got through by overtaking on the wrong side of the road at speed, and then by cutting up the side alleys, Steve McQueen like, squeezing past vegetable delivery trucks, crossing over the ridge of a hill dense with houses and then dropping down into the university quarter.

Later, after we’d checked into our new hotel, we walked through the steep streets towards the Blue Mosque. I hadn’t realised Istanbul would be so hilly, or that there would be constant views of the sea glimpsed between buildings on this southern side of town. The geography of the place springs surprises on every corner.

We passed a mosque on a little street and looked down into a gloomy, forgotten graveyard next to it, and then found ourselves suddenly in a wide and grassy space, which I quickly realised was the site of the Byzantine hippodrome. All that’s left of the ancient race track now are two obelisks which stood there in Byzantine times. At the base of one of them is a sculpted block from AD 390, which still shows the emperor in the kathisma, his trackside box, surrounded by VIPs and holding out the wreath of victory.

We walked on and had our first view of Hagia Sophia (seen above) across gardens with a fountain, everywhere crowded with people. The old church turned mosque turned museum looked dense and massive – and quite ramshackle in a down at heel and homely way. All around, street vendors were selling roast chestnuts and corn on the cob from brightly coloured carts.

It was 5 o’clock and the church was closing for the night, so we walked right around it, admiring the Hag-tat on sale, including t-shirts and postcards, snow domes and souvenir miniatures of the holy building. Plus harem pants and fez hats and trinkety jewellery. We saved our Turkish lira for tomorrow and found some supper at the Sultan Pub, which has a fine roof terrace overlooking this old part of town.

Comment (0) |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Flying to Byzantium

Posted on 02 October 2010, 4:44

Flying to Byzantium: Entry 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | Photos

Tomorrow morning at dawn I fly to Byzantium with my daughter Tali for a couple of days in the great city. I always had in mind that I’d travel there by train, as I wanted to feel each hill and bump of the earthly connection between London and Istanbul… but also to allow for some time-travelling between the world of now and the world of then which Constantinople represents for me. It takes three days and several hundred pounds to go by train, though, so BA flight 678 it is.

I’ve wanted to go there since I was 12. That’s when I first read about the city and got bewitched by it in Henry Treece’s brilliant A Viking Saga, in which the Viking heroes end up in Miklagard – how many names can one city have?

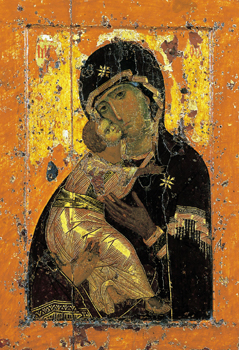

But since then, I’ve grown to love Byzantium because Eastern Orthodoxy fed me spiritually for years, throughout the 1990s and into the 2000s. I loved and drew on the alluring mysticism of icons and Eastern liturgy, and Byzantium was the geographical centre of that world. It was there that one of the most beautiful icons of all, the Virgin of Vladimir (seen above), was created and then sent into pagan Russia to help form Russian Orthodox spirituality.

I’m looking forward to standing in Hagia Sophia, the Church of the Holy Wisdom, and paying my respects. The church, built in the faraway 6th century, is more than half a millennium older than Chartres Cathedral. But there’s also a smaller church near the city walls with a fresco of the resurrection which I’m anticipating will be a demanding spiritual encounter.

Byzantium is a place of meeting and conflict between Christianity and Islam – just the conflicting names of the place tell their own story. Someone today on Twitter told me, ‘Don’t call it Constantinople, the Turks get very pissy about that.’ So I’m hoping also to get a better understanding of this place where the tectonic plates of faith get frictive with each other.

Comment (0) |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|