|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Category: Istanbul

|

|

|

|

Heaven and hell in a country church

Posted on 09 October 2010, 4:47

Flying to Byzantium: Entry 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | Photos

Istanbul, Sunday: Tali and I emerged from the depths of Hagia Sophia and went to sit in the open air café in the gardens outside for a calming cup of coffee and cigarette after all that religious intensity. I don’t normally smoke, but it was definitely time for some nicotine-assisted reflection.

Meanwhile, great dollops of beautiful warm sunshine were being generously served up on Istanbul, and after a quick visit to a cash machine, followed by a stroll among the underground pillars of the Byzantine cistern of Yerebatan, which is across the road from Hagia Sophia, we jumped into a yellow taxi.

‘Can you take us to the Chora Church?’ I asked our small, moustachioed driver. ‘Yes,’ he replied. And then sped off in the opposite direction to the church.

There followed some back seat angsting over whether we were being taken for a ride, until our driver explained that the police had closed the obvious routes because the town was choked with tourists. We drove around the Saray point and up the Golden Horn, with more than enough to look at on the way: towering, historic mosques, noisy, colourful markets, people enjoying lunch on the street, sticking their faces into chicken kebab wraps, ferries roaring out into the lively waters around the Galata Bridge.

Ten minutes later and we swept left along a broad road and were suddenly alongside the massive medieval walls of Constantinople, looking at them from the outside, just as the Ottoman attack troops had done before the city fell to them in 1453. And then left again, through a great breach in the walls, and we dropped down a narrow street to St Saviour’s, the Chora Church.

One of the meanings of chora is ‘country’, and as this whole area was rural even into the 20th century, the Chora Church is basically the ‘country church’. Which sounds very sleepy to English ears – and there is something country in feel about this place. It has a shady, walled garden at the back, and over the wall I could hear a children’s playground. But far from being just another country church, St Saviour in Chora is a jewel of Byzantine art: rebuilt in the 11th century and then decorated with the most stunning mosaics and wall paintings during a six-year makeover in the 14th century.

If that sounds a bit serious, then stepping inside makes you realise it’s entertaining, too, because the scenes covering the walls and ceilings of this lovely building are full of incidental detail: the water jars being topped up at the wedding feast of Cana; children playing on the edges of the crowd in the feeding of the 5,000; an angel carrying a giant scroll with the sun and moon rolled up in it at the last judgment. This is medieval television and the glass pixels in the mosaics are tiny enough to make it hi-def.

As you walk into the church, you pass beneath a monumental head and shoulders of a fierce-looking Christ. This is titled, ‘Jesus Christ, the chora (land) of the living’. So you enter under a theological pun which plays with the church’s name and the words of Psalm 27: ‘I am still confident of this: I will see the goodness of the Lord in the land of the living.’

But the face remains powerful. In her book, The Irrational Season, Madeleine L’Engle describes visiting the Chora Church and seeing this image of Christ. She says, ‘I knew that if this man had turned such a look on me and told me to take up my bed and walk, I would not have dared not to obey. And whatever he told me to do, I would have been able to do.’

Like Howard Carter at the opening of Tutankhamen’s tomb, we saw ‘wonderful things’ as we walked around, but I was here mainly for one wonderful thing: a fresco I had seen long ago in a book and which has lodged in my heart and head ever since. I saved it for last. It’s in the church’s burial chapel, painted inside the half dome at the east end, filling the whole of that curved space.

Standing dead centre beneath the icon, Tali and I looked up and became for the moment its intended viewers. Its title is Anastasis, ‘The Resurrection’, and in it the most alive Christ you’ve ever seen strides through hell, seizes Adam and Eve by the wrists – just as you’d grab the wrist of a difficult child – and pulls them bodily from their tombs. Beneath his feet are the trashed gates of hell, and below that is Satan, bound like a slave and surrounded by broken locks, chains, jailer’s keys and other small debris from the infernal workshops.

But it is Jesus who commands the scene, and your attention. I’ve never seen him painted this way. Byzantine icons are famously formal and still, with the look of people who have been told to hold a pose and not move. But this Jesus is caught in swift and decisive movement. He captures the vigorous words of the Orthodox Easter liturgy…

Christ is risen from the dead,

trampling down death by death,

and to those in the tombs he has given life.

This is so far from the seven-stone weakling Christ I saw pinned up in Sunday school in the 1960s, and so far from the bleeding victim Christ of Catholic statues which weep, that it took my breath away when I first saw it. Like reading Mark’s Gospel, it made me want to follow Jesus then… and now.

Did Jesus rise from the dead? I don’t know. What I do know is that I’d trade just a glimpse of this image for a hundred evangelical books which try to argue ‘the case for the resurrection’ like a whodunit. The Christ shown here powerfully makes me want to believe, and my unbelief can go hang.

Having said all that, I stood still under the image: absorbed, gazing, listening in the few minutes of my life I was there. Madeleine L’Engle says she trembled with joy as she stood on the same spot. For me it was wonder freed from emotion, which I hadn’t expected.

I don’t know if I’ll ever be here again. But I live in the glow of it. I hope for the life and transformation promised here. I hope to be in the land of the living Christ.

Comment (3) |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Into the Mega Ekklesia

Posted on 06 October 2010, 7:19

Flying to Byzantium: Entry 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | Photos

Istanbul, Sunday: Up at 7.30, along the gloomy corridor to the hotel lift, and then up, the lift managing no more than a crawl, to the 8th floor. The doors opened and the sun burst in, and we walked out into a rooftop breakfast room floating above the city, with the whole sweep of the Sea of Marmara at our feet.

Tali and I sat dazzled by the light and hardly able to drag our eyes away from the view. The Marmara really is a handsome body of water, with the Prince’s Islands forming beautiful grey silhouettes in the eastern light, 10 miles distant across the silky water. The islands were so-named because unwanted minor royals were often dumped there in Byzantine times, with no access to Hello! or Grazia and the other essentials of celebrity.

Breakfast over, we took the tram to the Sultanahmet (the ‘Hippodrome’) district of town, which is the historic centre of old Stamboul. There we went straight to Hagia Sophia and entered the gardens on the west side, which have been turned into an orchard of ancient stone columns, each dug up at various sites around the city.

I could hardly bear to go into the Mega Ekklesia (the ‘Great Church’ as it was known almost from the time it was built in the 6th century), as I’ve imagined the moment for so long, so we loitered around the gardens first, admiring beautiful pieces of long destroyed buildings, some of them in such good nick they might just have come out of the sculptor’s yard.

But then we turned to the imposing doors and passed through the outer and inner porches and on into the church. The interior is such a delirium of space I had to lean against the doorway for the first few minutes to drink in what I was seeing.

Below, a polished marble floor of vast expanse; above, the dome ringed by its 40 windows, sailing weightlessly into heaven as it has done for 14 centuries; around me, a hundred arms raised… not in worship, but holding digital cameras. In the centre of the church, huge chandeliers hanging from the heights above to hover within touching distance of the people below, creating intimate pools of space.

Unlike all the domed cathedrals I’ve visited, here the dome is immediately visible from the church door, and so the visual impact of Hagia Sophia arrives at once, in a single, overwhelming instalment.

In the 10th century, a Russian prince sent ambassadors to Constantinople in search of a faith to replace his paganism. When they arrived in Hagia Sophia, they said, ‘We knew not if we were in heaven or on earth, for surely there is no such splendour or beauty anywhere upon earth.’

A thousand years on, and even though the church is now stripped of the Christian worship which once made it live, I can understand what they meant. Its vast spaces, its beauty and antiquity, even its faded grandeur and tangible sadness, all evoked in me the mystery and eternity which belong to God.

We walked up an ancient spiral ramp to the gallery, which gives stunning views down into the church. At this level you can see how the eight large medallions bearing Islamic calligraphy are constructed, each of them with a wooden framework. The medallions were only put in place in the 19th century by the Swiss architect tasked with restoring the building.

They complement the calligraphy right up at the highest point of the dome, which carries a famous verse from the Qur’an: ‘God is the light of the heavens and the earth’ (Surah 24:35). No Christian could argue with these words, but there is controversy over whether the calligraphy should be removed as it’s believed a much older mosaic of Christ lies beneath it. Christians of a more Puritan temper would probably side with Muslims on this one.

Beyond a marble screen in the gallery, I found the luminous icon of Christ which has been made famous on a thousand postcards, book covers and printed icons. The 14th century mosaic is next to a window and is thought to have been damaged by rain, so large areas of the jigsaw of tiny mosaic pieces are missing, but the heads of Jesus, plus Mary and John the Baptist, who stand on either side, are intact and beautiful. Each of them is shown against a glowing gold background in the world of eternity.

I was lost for a while in thought and maybe even prayer, standing before this noble and searching image of Christ. Just to stand before it is to be given dignity. And then I rejoined the crowd there, snapping like paparazzi before one of the surviving glories of lost Byzantium.

Comment (0) |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Welcome to a narrow paradise

Posted on 03 October 2010, 22:08

Flying to Byzantium: Entry 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | Photos

Acton to Istanbul, Saturday: Tali (my daughter) and I were late leaving the house to get to our local tube station, Acton Town, comfortably in time for the first tube of the day to Heathrow, so we had to do it the uncomfortable way instead: racing along the dark streets noisily dragging our cases-on-wheels behind us.

Even so, as we hastened I noticed the horned moon in the sky above us, a white, waning crescent. It struck me as a good sign for a trip to conquer Constantinople, as the moon was famously in this phase when the city fell to the Ottomans in 1453.

Five hours later we were hurtling in a taxi from the airport into Istanbul, rear seatbelts not working, Turkish music blaring, the meter ticking over gleefully. Suddenly out my window on the left I saw the brown and white stripes of the massive walls of Constantinople, where they come down to the Sea of Marmara, which was on our right. The walls finally failed in the Ottoman siege, which is why Istanbul is now a city of mosques rather than churches. I’ve always imagined entering the city from this side, through the walls, so this was an advance thrill of the city.

‘Welcome to paradise,’ was how the receptionist at our hotel in the old town greeted us, but paradise turned out to be a very narrow room: two beds with an 18 inch strip of carpet between them. So we were quickly back out on the street waving down a taxi for another hotel.

Our new taxi took us right around the end of the peninsula, giving us a lightning tour of the Bosphorus, packed with ships, and then the Golden Horn, with the coloured buildings of the Beyoglu district heaped up on the other side.

Our driver either hadn’t done ‘the knowledge’, or was deliberately taking us the most lucrative way around town, and we quickly hit the Istanbul rush hour. Which he got through by overtaking on the wrong side of the road at speed, and then by cutting up the side alleys, Steve McQueen like, squeezing past vegetable delivery trucks, crossing over the ridge of a hill dense with houses and then dropping down into the university quarter.

Later, after we’d checked into our new hotel, we walked through the steep streets towards the Blue Mosque. I hadn’t realised Istanbul would be so hilly, or that there would be constant views of the sea glimpsed between buildings on this southern side of town. The geography of the place springs surprises on every corner.

We passed a mosque on a little street and looked down into a gloomy, forgotten graveyard next to it, and then found ourselves suddenly in a wide and grassy space, which I quickly realised was the site of the Byzantine hippodrome. All that’s left of the ancient race track now are two obelisks which stood there in Byzantine times. At the base of one of them is a sculpted block from AD 390, which still shows the emperor in the kathisma, his trackside box, surrounded by VIPs and holding out the wreath of victory.

We walked on and had our first view of Hagia Sophia (seen above) across gardens with a fountain, everywhere crowded with people. The old church turned mosque turned museum looked dense and massive – and quite ramshackle in a down at heel and homely way. All around, street vendors were selling roast chestnuts and corn on the cob from brightly coloured carts.

It was 5 o’clock and the church was closing for the night, so we walked right around it, admiring the Hag-tat on sale, including t-shirts and postcards, snow domes and souvenir miniatures of the holy building. Plus harem pants and fez hats and trinkety jewellery. We saved our Turkish lira for tomorrow and found some supper at the Sultan Pub, which has a fine roof terrace overlooking this old part of town.

Comment (0) |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Flying to Byzantium

Posted on 02 October 2010, 4:44

Flying to Byzantium: Entry 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | Photos

Tomorrow morning at dawn I fly to Byzantium with my daughter Tali for a couple of days in the great city. I always had in mind that I’d travel there by train, as I wanted to feel each hill and bump of the earthly connection between London and Istanbul… but also to allow for some time-travelling between the world of now and the world of then which Constantinople represents for me. It takes three days and several hundred pounds to go by train, though, so BA flight 678 it is.

I’ve wanted to go there since I was 12. That’s when I first read about the city and got bewitched by it in Henry Treece’s brilliant A Viking Saga, in which the Viking heroes end up in Miklagard – how many names can one city have?

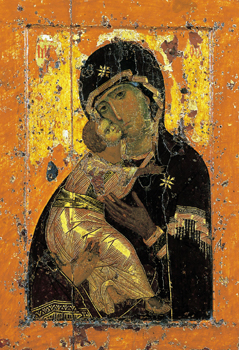

But since then, I’ve grown to love Byzantium because Eastern Orthodoxy fed me spiritually for years, throughout the 1990s and into the 2000s. I loved and drew on the alluring mysticism of icons and Eastern liturgy, and Byzantium was the geographical centre of that world. It was there that one of the most beautiful icons of all, the Virgin of Vladimir (seen above), was created and then sent into pagan Russia to help form Russian Orthodox spirituality.

I’m looking forward to standing in Hagia Sophia, the Church of the Holy Wisdom, and paying my respects. The church, built in the faraway 6th century, is more than half a millennium older than Chartres Cathedral. But there’s also a smaller church near the city walls with a fresco of the resurrection which I’m anticipating will be a demanding spiritual encounter.

Byzantium is a place of meeting and conflict between Christianity and Islam – just the conflicting names of the place tell their own story. Someone today on Twitter told me, ‘Don’t call it Constantinople, the Turks get very pissy about that.’ So I’m hoping also to get a better understanding of this place where the tectonic plates of faith get frictive with each other.

Comment (0) |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|