|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

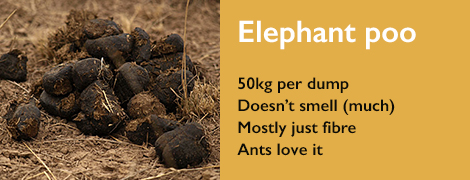

I took the ‘Which animal dropping are you?’ quiz and got ‘Elephant poo’

Posted on 13 April 2014, 10:28

Facebook has been swamped for a while with quizzes asking, ‘If you were a flower, which one would you be?’

Or which Muppet, prime minister, pop diva, Game of Thrones house, religion, 80s hunk or (Lord have mercy) character from Sex and the City are you? The question, ‘Which city should you actually live in?’ has apparently been liked on Facebook 2.5 million times.

So in an effort to maintain satire levels on Facebook, here’s my proposed quiz.

There’s an interesting piece on Slate about the phenomenon.

Comment (0) |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

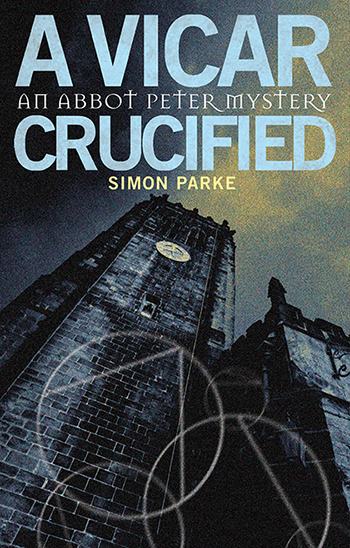

A Vicar, Crucified

Posted on 15 June 2013, 21:35

It’s not often a book keeps me up late three nights in a row, but A Vicar, Crucified by author Simon Parke kept sleep at bay this week where lesser books have failed.

It’s a murder mystery novel with a plot that has more twists than a hangman’s noose, written by a former vicar who has the inside story on the many reasons why parishioners might reasonably want to murder their priest.

On the murder most foul scale, this is close to the far end of foul, with flippant priest Anton Fontaine, vicar of St Michael’s Stormhaven (a quiet south coast town), nailed to a cross in his own vestry after the mother of all church meetings. The cast of suspects includes Bishop Stephen, who elevates himself by putting others down, Curate Sally, who likes to demonstrate she’s in charge, and youth worker Ginger, whose temper is on a hair-trigger.

Helping the police with their enquiries (as witness rather than suspect) is Abbot Peter, recently returned to Britain from running a monastery in the Sinai Desert. And helping him is the enneagram, the psychological profiling tool which gives the Abbot deep insight into the motivations of the suspects.

The dialogue of the novel is especially satisfying for anyone who fantasises about telling others exactly how irritating they are. ‘I sometimes wonder if you belong here, Peter?’ the Bishop tells the Abbot in a savage moment of passive aggression. ‘Have you ever thought of going somewhere you matter?’

Simon Parke, before he did his vicaring, was a scriptwriter for Spitting Image, and his satirical instincts are on fine display in the novel.

Most of all, though, I enjoyed the psychological insights of the book, with Abbot Peter lifting the lid on his fellow human beings as they manipulate others and reveal their own desires. That gave me plenty to think about when I wasn’t engrossed in the plot or trying to beat the Abbot in the race to discover the murderer. Which I didn’t, of course.

A Vicar, Crucified is the first in a series of at least three Abbot Peter novels, the second, A Psychiatrist, Screams, having just gone to the printer. I’m looking forward to some more sleepless nights when it’s out in the autumn.

Comment (0) |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Lives of the coin-operated saints

Posted on 01 June 2013, 20:39

I’ve never seen a saint bashing herself in the face with a pair of pincers before. But as I entered Michael Landy’s Saints Alive exhibition at the National Gallery this morning, there guarding the way in was a 3 metre tall St Apollonia, in a floor-length red dress.

You press the foot pedal at her feet, and lo! The pincers she holds with both hands jerk upwards into her face with a crash, powered by the wheels and cogs in her chest. All that’s missing is the opening of the Monty Python theme tune.

Michael Landy is famous for destroying all his worldly possessions in an installation art event called Break Down in 2001. He was invited to be the National Gallery Associate Artist three years ago and in that time has sampled and remixed images of martyred and wounded saints from the gallery’s huge collection of Renaissance paintings.

With the help of old prams wheels and bits of machinery salvaged from skips, flea markets and eBay, he’s turned the saints into large sculptures which alarmingly whirr into life at the kick of a pedal.

There’s a lovely bust of St Francis gazing adoring at a crucifix held close to his face. You pop a coin in the slot and the crucifix whacks him in the face. There’s a torso of St Jerome connected to a muscular arm holding a big stone. Hit the big red button on the floor and the arm bashes the stone into the chest.

This alarming sight is taken directly from the story of the saint taking his mind off the dancing girls of Rome in the way he found most effective. It struck me that the sculpture will probably destroy itself before it gets to the end of the exhibition’s six-month run. The torso is only glass fibre after all.

I’ve never seen anything like this unlikely marriage of Catholic piety and amusement arcade, and it provokes an equal dose of comedy and reflection.

Michael Landy, who was brought up as a London Catholic to Irish parents, is struck by the way the lives and sufferings of the saints, once popularly known through The Golden Legend and other books, have now passed out of popular (and even religious) culture.

Landy could have chosen all sorts of saints from the National Gallery collection, but as he says, ‘I chose the more destructive saints’. He was especially drawn to St Francis, as people drew a parallel between the self-sacrifice of Landy’s Break Down and Francis during the 2001 event.

Landy says: ‘When Francis sees someone wearing worse rags than him, he’s envious of them. We’re all envious, you know. The more stuff people have, the more successful we see them in our society. Saint Francis is the reverse. He wants your rags.’

In that sense, Saints Alive is an artistic take on people who were counter-cultural, who were determined to follow their faith to the point of self-destruction. ‘The saints are all very single-minded individuals. That’s what I like about them,’ says Landy.

Two of the exhibits were out of action this morning, one of them a headless, kneeling figure of St Francis, hollowed out. A mechanical grab suspended above the figure lowers into the body and if you’re lucky comes out with a t-shirt you can keep. The t-shirt has a drawing of a knotted rope with the words, Poverty Chastity Obedience.

I overheard a member of staff talking about the mechanical breakdowns and asked him about it.

‘I’ve been here a week,’ he said, ‘and every day at least one of the sculptures is broken. The machinery is made of salvaged motors and they’re not up to being operated so many times a day.’ They’re now waiting for new motors, so hopefully the saints will be moving mightily again soon.

He very kindly allowed me to take some pictures, despite the gallery’s no photography policy.

In keeping with the exhibition’s destructive themes of self-sacrifice, torture and martyrdom, Landy’s intention is that the sculptures will gradually wreck themselves, and the frequent collapse of second-hand components is probably part of that too.

It’s also a very good marketing ploy. I want to pay a second visit to have a go at getting that t-shirt.

Saints Alive by Michael Landy is at the National Gallery, London, until 24 November. If you can’t get there, the exhibition catalogue is worth ordering (£9.99).

Comment (0) |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Remembering our dog Sasha

Posted on 27 May 2013, 4:50

She and I walked every weekday in the big spaces of Gunnersbury Park.

Late spring mornings, warm enough to tempt her into the pond for a swim. Lazy summer evenings, when she kept a sharp lookout for abandoned picnics on the grass. Gloomy ends of day in autumn when we walked the paths alone with mist filling the hollows. Winter days when she wore a flashing collar for the dark.

Her habitual sin was hanging back. She hung back in her endless quest for food. She was one-third Labrador, you see, even though she looked like a large fox.

She hung back so much, I spent half my time looking over my shoulder to check she wasn’t so far back that I couldn’t see her.

And generally there she would be, 100 metres distant at the least, her nose to the ground like a Hoover, her ears pricked forward, her splendid, bushy tail held high and proud as she brisked back and forth over the grass on a very promising scent.

But there could be the most amazing reward for all this looking back. If you called her name and threw your arms wide and held that scarecrow pose, she would break off her hunt, tuck her legs under her body and fly towards you like nothing else in the world mattered.

It was her sprint of joy.

Because as she closed the distance between her and you, there was intentness and joy in her face and eyes and in the way her shoulders and bottom bounded up and down. I always squatted down to her height, arms still thrown out, as she made her final approach, and then she’d fly past me, or run alongside if I pretended to flee from her.

She made me feel in those moments the physical exhilaration of being alive. I loved that shared creatureliness, where she was so much more than me.

Back home, she wasn’t much of a one for physical contact. She was reserved and liked her own space. But she allowed us to stroke and fuss over her.

She nibbled her front claws so loudly sometimes you could hardly hear the TV. Lying in the dark in the middle of the night, hearing her deep breathing or snoring, in her bed next to ours, was comforting.

Her ears were long and silky and sometimes went inside out. But we taught her to shake her head when we said, ‘Your ears are inside out.’

Roey took her to training classes when she was a young pup in the late 90s, and then to dog agility classes, and found she loved learning. Somewhere I have a list of 60 words and phrases we collected which she understood. I’m sure this isn’t unusual for intelligent dogs, but it’s just part of our story with her.

After she died, a year today, I carried on walking the park. Those first walks were hard. I walked looking back for her. Through the long avenues of trees, where I had so often glimpsed her in the green distance as she unhurriedly caught me up, she failed to appear.

I watched for her to amble from behind a tree trunk, late as usual, but she just didn’t.

I cried for her a great deal. I knew I would cry, but I didn’t know how much. I didn’t know how much it would hurt.

Somehow, in our lovely dog who was strong, fast and beautiful, but also vulnerable and uncomprehending of this world, in need of our love and protection, my griefs and sorrows were gathered up together.

I will always remember her, look back for her, throw my arms wide for her.

Comment (2) |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

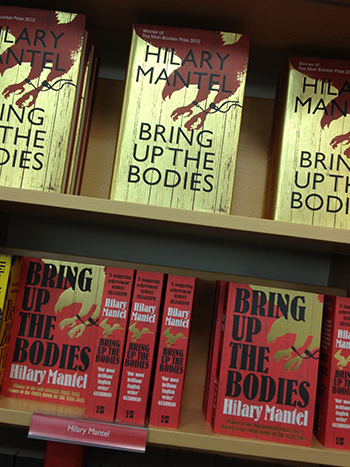

Bring Up the Bodies

Posted on 09 May 2013, 1:49

A new book came out yesterday… except, hang on, it isn’t new.

Bring Up the Bodies is the sequel to Hilary Mantel’s brilliant Wolf Hall. It was published a year ago in hardback, and since then there have been book reviews (last May), Mantel’s winning of the Man Booker prize (last October) and of course 12 full months.

And now, finally, publisher Fourth Estate has released the paperback edition. I snapped it today in Foyles bookshop next to the hardback (pic above).

I understand why publishers produce hardback editions first – they want to maximise profits when their star books are in the spotlight and calculate their paperback print-runs intelligently. The hardback of Bring Up the Bodies is currently retailing at £20, twice the price of the paperback (£9.99).

But making readers wait a full year before releasing such a culturally significant and widely discussed book just seems greedy to me. And it surely can’t be great for the book either, since those of us who would like to talk about it but aren’t on the freebie review copy lists of Fourth Estate will only be getting our teeth into it this week.

I’d like to talk about what’s inside Bring Up the Bodies, since I found Wolf Hall such a powerful and almost unmediated doorway into past lives. But I’m wondering, why bother, a year later?

Comment (0) |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|